Harvey Dunn’s Legacy

In the Lalor Library Media Center, there can be found a little-known treasure---nine paintings of Abraham Lincoln by an American master painter.

May 1, 2018

It’s easy to overlook the Lincoln paintings hung up on the walls of our very own Lalor Library Media Center. Large and imposing as they may be, their admittedly drab colors make it a challenge to notice them during a busy day. However, understanding their origin and creator gives good insight into the history of our school. And a closer look at these paintings shows them to be a treasure unrealized by many.

Our story begins in 1884 with Harvey Thomas Dunn, born on a simple farm in South Dakota. After attending South Dakota State University, with encouragement from his instructor, Ada Cadwell, he furthered his education at the Chicago Art Institute. During his time at the Institute, he met and later studied under Howard Pyle, one of America’s most popular illustrators and authors at the turn of the nineteenth century. Dunn then began his professional career in Wilmington, Delaware, illustrating for various magazines. Despite his love of illustration, his interest turned to teaching students—just as Caldwell and Pyle had done for him—so in 1914, he moved to Leonia, New Jersey and started the Leonia School for Illustration. However, his life drastically changed as the country headed towards the First World War. After being chosen to take part in the American Expeditionary Force in Europe, Dunn had to record the war for different historical and propagandistic purposes. Though he was one of the first men to return to the States, staying in Europe for less than a year, he continued illustrating his war experiences for many years. It was said that the war changed him; when he returned from it, he moved to Tenafly and became a far more dedicated art teacher. He would later be described as being strict and demanding, but this was all in an attempt to prepare his students for the competitive and commercial art world. He was, however, addled with health complications, and unfortunately passed away in 1952.

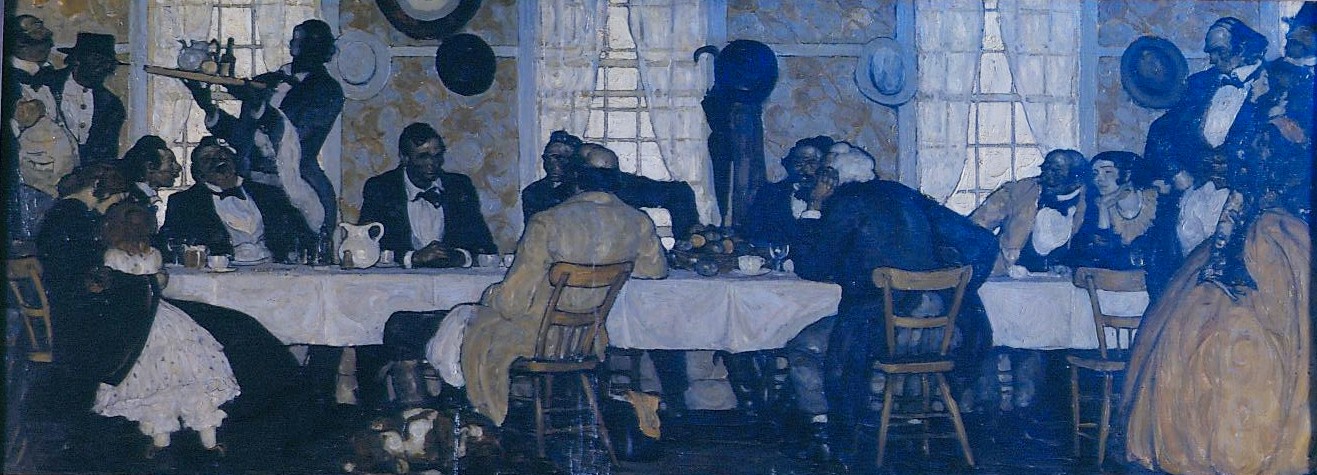

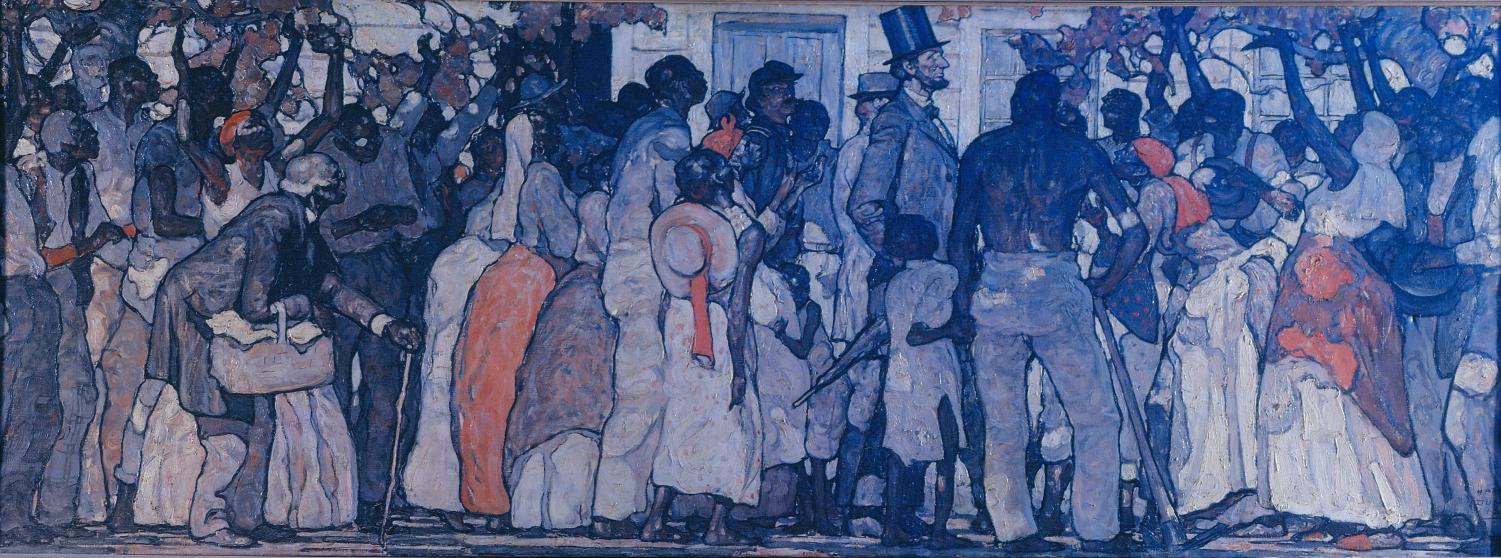

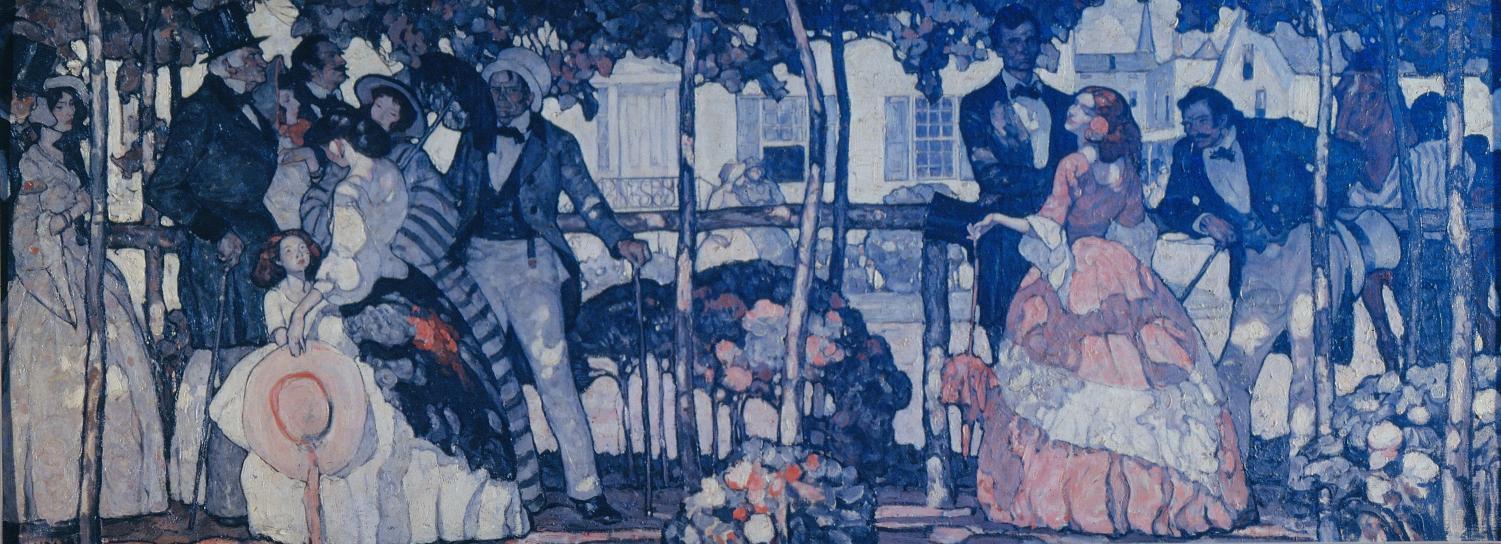

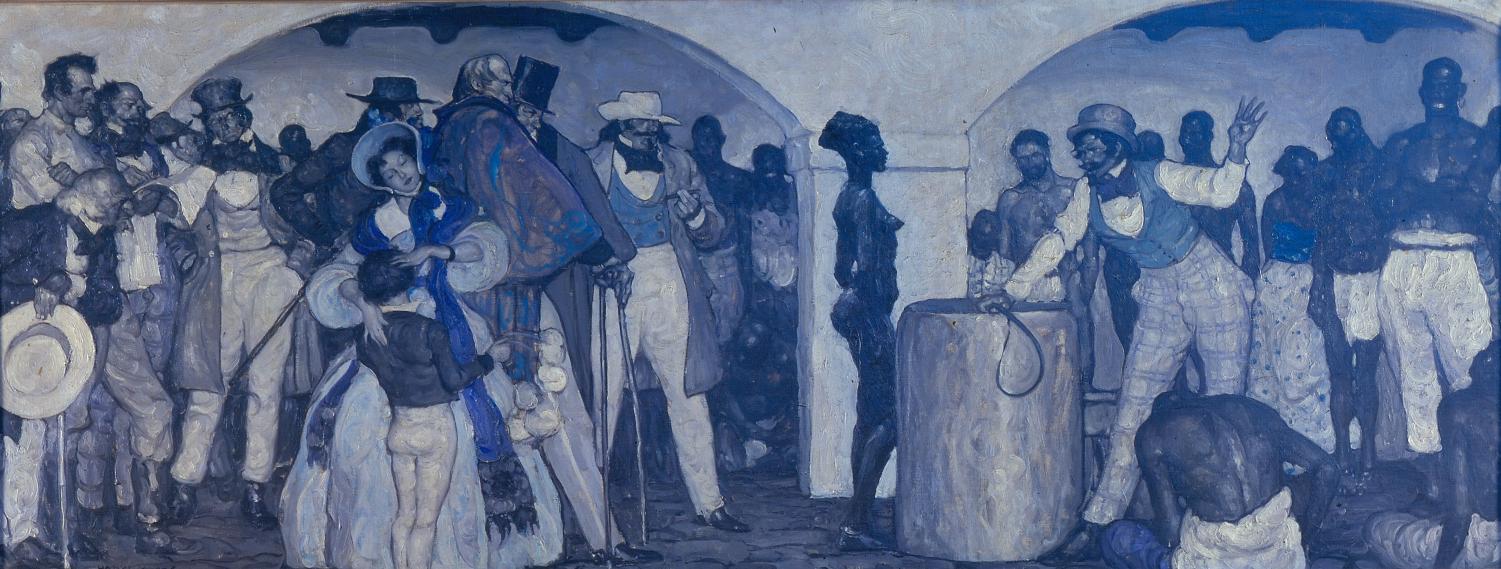

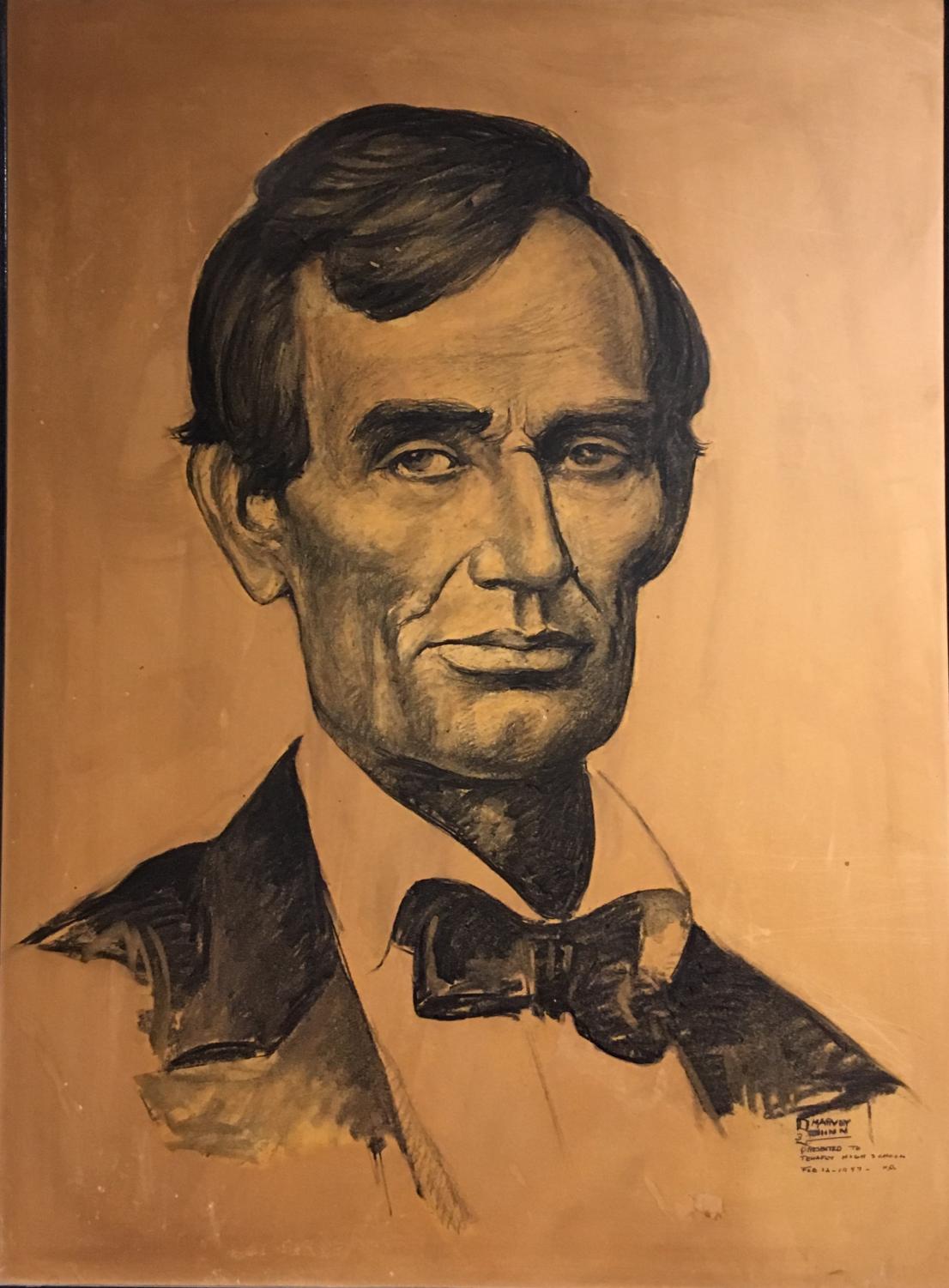

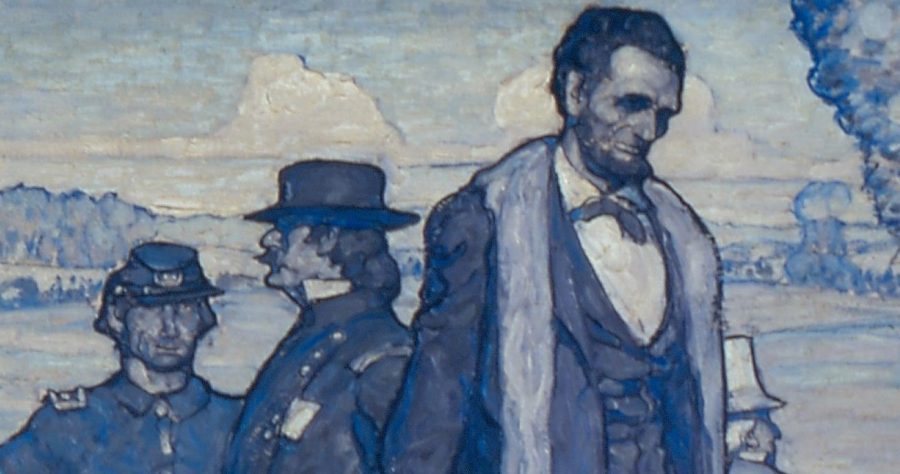

Despite his death, Dunn lived on—not only in his students but his art as a whole. This brings us to the Lincoln paintings. How did they get to the school library in the first place? According to letters passed along between the former THS principal, Howard Pordy, and a friend of Dunn’s, Robert Karolevitz, the paintings were exhibited in the high school because the former didn’t want them to remain hidden to the world within Dunn’s studio attic. It appears that the paintings were created for issues about Lincoln in the magazine Cosmopolitan (which can be found in the library), which would explain their color tone. When asked if he could move them, Dunn simply replied, “Hell, nobody’s interested in these pictures,” and refused. He later relented to letting Pordy borrow them for a “little while” to see if “anybody [would be] interested in them.” According to Pordy, “many people came to see the pictures from far and near,” and upon hearing this Dunn “never once showed any particular pleasure or pride [in the paintings] but never once did he say one word about removing them.” Notwithstanding that Dunn seemed apathetic towards his art, he insisted on hanging up the paintings alone. It would seem that he, at the very least, had pride in his art. Interestingly, the documents in the Lalor Library Media Center collection also reveal that a ninth painting, “Lincoln-Douglas Debate,” is missing and purportedly stolen. The eight remaining Lincoln oil paintings, each measuring 81×30 inches, hang on the east and west walls of the library. There is also a portrait of Lincoln, measuring 28×38, in the teacher’s Cyber Cafe adjacent north to the main library. While the paintings are in need of a thorough cleaning after decades of collecting dust, a closer look reveals them to be museum-quality pieces by an American master.

Perhaps the clearest characteristic of Dunn’s art is its simplicity. Though he may have strayed far from his modest farmland origins, it’s obvious that he integrated the same plainness in his paintings. According to his contemporaries, the same could be said about his lifestyle and philosophy—he wasn’t an exceedingly complex person. Some might even call him outdated. However, I believe that beyond Dunn’s straightforward persona was a man of deep wisdom, and perhaps that’s what the Lincoln paintings were supposed to convey—that there’s more to them, as with Dunn, than meets the eye.

The Lincoln paintings: