Grade inflation is very similar to financial inflation in that both are crises, yet grade inflation often receives less attention.

Just as financial inflation occurs when the prices of goods rise, leading to a decrease in the value of money, grade inflation happens when the number of high grades increases, therefore decreasing the value of those grades.

In 1998 the average GPA for high school students was 3.27, but since then, it has risen by more than 0.10 points, according to USA Today. This could suggest that students have miraculously become smarter in the last 35 years, yet that’s very doubtful, especially since average SAT scores have dropped from 1026 to 1002 over the same period of time. Additionally, ACT scores in 2023 have reached their lowest point in the past thirty years. These trends reflect how grades assigned by teachers have risen, yet student performance on standardized tests that have been unchanged for decades have declined.

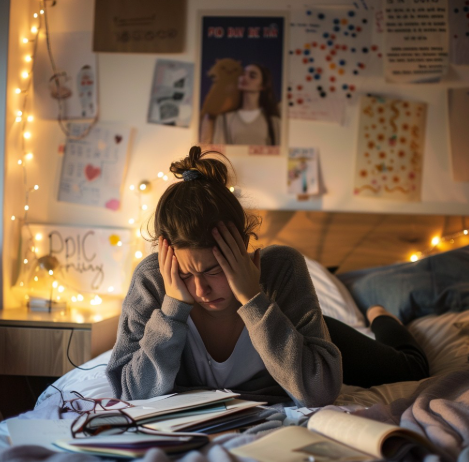

As high school students, we accept that standardized tests are an essential part of our education. We study for weeks or even months, and we put in hours of dedication on every little detail our teachers have imparted throughout the year. However, when the data that represents students’ performance is inflated, it undermines their ability to study to the best of their efforts. When a student’s grades are high on average, it could give the student a false measure of his or her actual ability in school. Thus, when the SATs and ACTs come around, students underestimate how much they need to study, consequently causing them to perform poorly on the tests.

Furthermore, most universities currently are making standardized test submissions optional. While this policy may have its advantages, a significant disadvantage would be that if students have grades that are too high for them, the university receives an inaccurate understanding of its applicants. If a university receives a false impression that students have high enough grades for its institution, these students may find themselves overwhelmed at the school, and have a hard time adjusting.

In an article from the The New York Times, Tim Donahue, an English teacher in Connecticut, explains why he thinks grade inflation has been so bad in recent years. “It’s just so much easier to give good grades!” He explains that he understands how hard students work from starting the day at 7:30 in the morning and finishing at roughly 7:30 at night, comparing this time to the amount of time “it takes someone to complete a full Ironman triathlon.” Thus, he feels sympathetic to how much effort students put into their schoolwork, which makes assigning a low grade painful.

While the opposing view is that grade inflation is good because it reduces stress and anxiety for students, according to The Daily Universe, this position is ultimately wrong.

While reduced academic pressure is, for the most part, beneficial, grade inflation causes more harm than good. There are other ways to reduce the academic stress for a student that does not involve inaccurate grades.

All in all, grade inflation has negative long-term effects. When a student transitions into the workforce, there’s a high probability that the student will underestimate the difficulty of the situation due to him or her being accustomed to getting high grades with work that might not deserve that grade. Therefore the student will most likely fail, since in reality, a boss won’t assign a bad grade; they will simply fire a poor worker.