On November 27, the Islaimst anti-government group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and its allies overthrew Syria’s dictatorial regime under Bashar Al-Assad through a surprise offensive. HTS took advantage of dictator Bashar Al-Assad’s weakened authority and distracted allies to rout government forces and occupy the country’s largest cities. Assad’s government was a significant regional enemy of the United States due to its alliance with hostile states such as Iran, as well as being a center of terrorist activity., A major geopolitical event, this remarkable campaign concluded in less than two weeks, leaving a pressing question for onlookers: how did HTS and some of its allies accomplish what the US-backed Syrian rebels couldn’t for over a decade?

For context, the Assad family ruled Syria for 53 years, with Bashar Al-Assad taking power in 2000. According to The New York Times. Assad has an extensive record of ruthless oppression, from brutally crushing a pro-Democratic uprising in 2013 during the Arab Spring to triggering civil war and sharp emotions which continue to this day. Although rebels, especially U.S.-funded ones such as the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), had some initial success in capturing government land, Assad and his allies eventually retook much of Syria, save northern and eastern areas controlled by a Kurdish-led rebel alliance. HTS broke off from Al-Qaeda in 2016 after being founded as the Al-Nusra Front in 2012. It consolidated regional power by eliminating rival extremist and rebel groups, controlling “much of northwest Syria and in 2017 set up a “salvation government” to run day-to-day affairs in the region,” according to AP News. It also states that in order to attain regional legitimacy, “[HTS’s] leader Abu Mohammad al-Golani has sought to remake the group’s image, cutting ties with al-Qaida, ditching hard-line officials and vowing to embrace pluralism and religious tolerance.”

Syria’s civil war, thought to have been in a stalemate, sparked to life when HTS and other rebel factions started an offensive in the north-west. According to the BBC’s David Gritten, HTS claims that their offensive was launched to “deter” current “aggression” against peoples in north-western provinces by Assad and Iranian-backed militias. Additionally, The New York Times reports that Lt. Col. Hassan Abdulghany, military commander of the combined rebel forces has claimed, “‘…this operation is not a choice,’” adding that “‘It is an obligation to defend our people and their land. It has become clear to everyone that the regime militias and their allies, including the Iranian mercenaries, have declared an open war on the Syrian people.’”

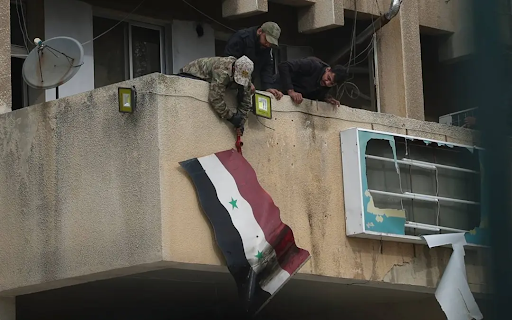

Starting off strong, HTS took control of Aleppo on the 30th of November, the second largest city, with the help of allied factions. Only three days after the surprise offensive began. Gritten reports that “[the HTS] faced little resistance on the ground after the government rapidly withdrew its troops and security forces.” This move was as symbolic as it was strategic, Aleppo having been a major stronghold for Syrian rebels before it was retaken by Assad’s forces.

Afterwards, HTS made use of Syria’s highways to quickly move on to other major cities AP News proposed as an explanation for their “lightning fast” campaign. The city of Hama fell on December 5, followed by Daraa on December 6 and Homs on December 7, marking a “death spiral” for the Syrian state in the words of Middle East analyst at Century International Aron Lund.

The Washington Post, which interviewed Lund, also highlighted that the rapid nature of HTS’ advance and its newfound cooperation and coordination with allies constituted its eventual victory. Additionally, the BBC further reinforced the importance of the rebels’ speed, stating that “without [the] group’s sudden, devastating advance on Aleppo and then into Hama and Homs from their powerbase in the north-western province of Idlb, there is no doubt that the tumultuous events of the past week and a half would not have happened.” However, HTS’ success could not have been achieved if the Syrian government’s allies were more involved, with CBS News reporting that the offensive occurred at a time when Assad’s closest partners were “preoccupied with their own conflicts.” Russia, although having sent a meager number of warplanes to harass the rebel advance, was busy in its war against Ukraine. Iranian-backed militias in Syria supporting Assad were cut off from being supplied by frequent Israeli strikes. Moreover, Iran’s presence in Syria was greatly diminished by the April killing of Iranian commanders in Iran’s Syrian embassy as reported by Reuters. Finally, Israeli attacks on Hezbollah in southern Lebanon weakened another key ally of Assad, with the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) claiming that, “ Against the backdrop of Hezbollah’s diminished position in Lebanon, along with the significant hits it has taken to its positions and arms supply in Syria, Syria’s rebels seized the opportunity to launch their assault on Aleppo.” In all, USIP’s Mona Yacoubian writes that beyond regional geopolitics, the desperate condition of the Syrian economy and the miserable humanitarian conditions in the country brought a “hollowed” out regime to its last breath. HTS’ campaign was simply the straw that broke the camel’s back.

With the capture of several of Syria’s major cities, economic zones, industry, and key infrastructure, as well as firm control over the surrounding suburbs, HTS turned its eyes to Assad’s capital: Damascus. The lead up to the battle for Damascus, however, is just as important as the final blow to the Syrian dictator’s regime. HTS’ lightning-fast offensive shows how seemingly intimidating states can be more vulnerable than they show. Additionally, it highlights the importance of allies in any conflict, even for a strong regional power. With the capture of Damascus have already concluded, it’s still important to recognize the steps HTS had to take in order to challenge Assad’s greatest stronghold, and why the rebels felt so motivated in the first place.