Aaron Sorkin’s To Kill a Mockingbird: A Masterpiece

March 2, 2020

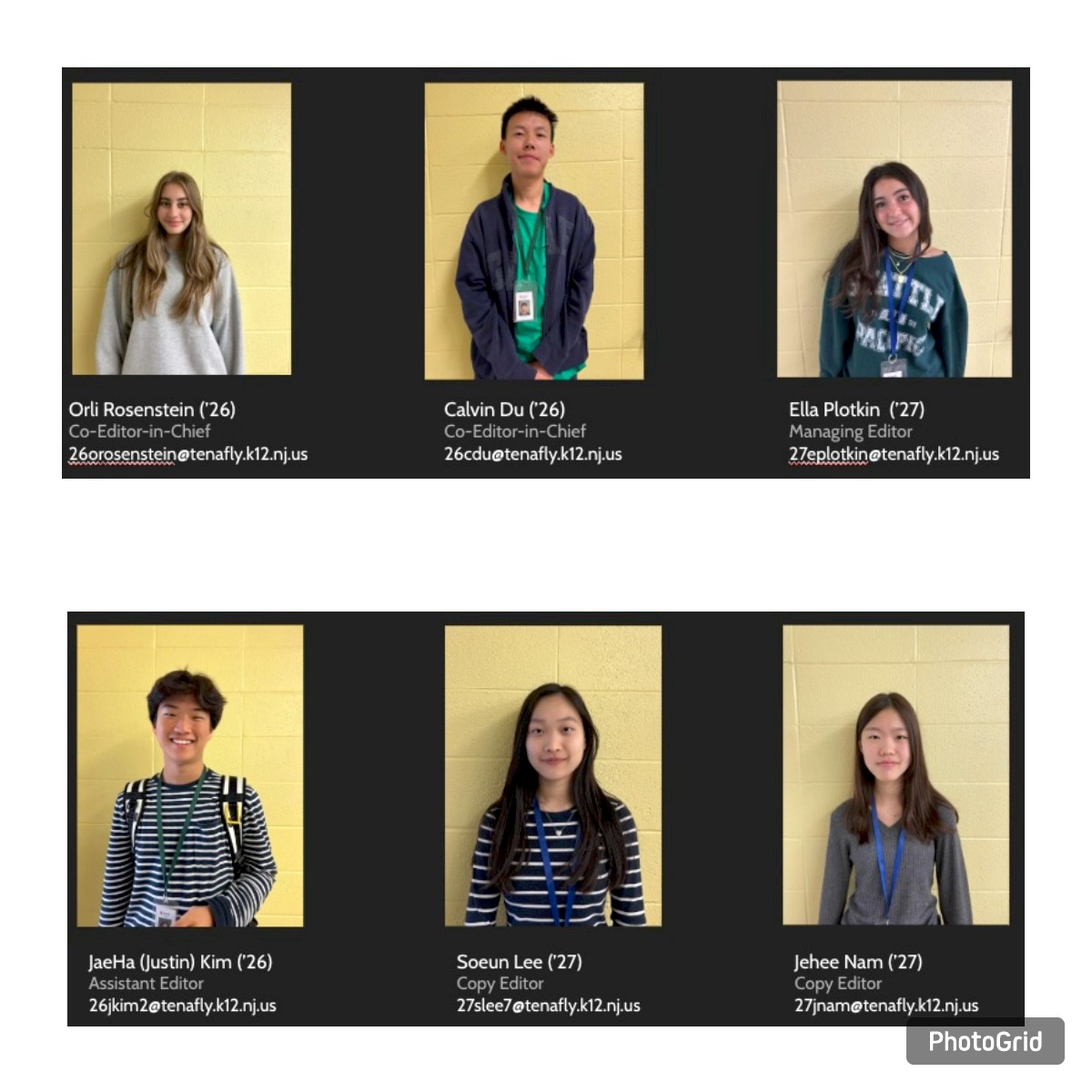

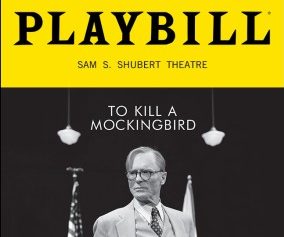

On Wednesday, January 29th, the AP Language and Composition classes, along with some seniors from the AP Literature and Composition classes, took a field trip to New York City to watch Aaron Sorkin’s theatrical adaptation of Harper Lee’s best renowned novel, To Kill a Mockingbird. The rationale for seeing the play, besides its obvious appeal as an adaptation of a classic and popular novel, was that Tenafly alum Ed Harris was starring as Atticus Finch. Harris has had a storied career both on the silver screen and the stage, having starred in everything from The Truman Show to Westworld, and being able to see him perform live was an undeniably amazing opportunity. After the play, students were also able to participate in a talkback with the actors and learn more about the nooks and crannies of Sorkin’s play.

Personally, before watching the play, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect of it. When I read To Kill a Mockingbird in eighth grade, I fell in love with the nuanced plot, rounded characters, and surprising ending. While many other childhood favorites fell to the wayside as I grew older—from rainbow sprinkles to Lunchables—To Kill a Mockingbird held up. When I reread it in high school, I found it to be just as touching as it was the day I opened it in eighth grade.

As a result, I was a bit wary of what the production would bring. Would it, like the uncovered “sequel” to To Kill a Mockingbird, Go Set a Watchman, change my perception of Atticus Finch—and thus the novel—forever? Would it be too heavy-handed in its messaging? How could a play give its audience the same insight into Scout’s state of mind as a first-person narrative?

But these doubts were all laid to rest the moment the curtain went up and the play began. Sorkin tells his adaptation of the classic novel non-chronologically, and the beginning is, in all honesty, a bit chaotic: all at once, Scout, Jem, and Dill seek to find the “beginning” of their tale, and this chaos (which is certainly welcome!) continues to have a place throughout the play. Unlike Lee’s novel, which occurs over the period of three years, the events of Sorkin’s play take place largely over one summer, yet fortunately none of the characterization of the original is lost. Although Scout (Nina Grollman), Jem (Nick Robinson), and Dill (Taylor Trensch) are all played by adult actors, they perfectly embody their characters, giving them each a childlike innocence that makes their performances convincing, not cringeworthy. The friendship between the trio is entirely convincing, and it provides some of the best moments of levity throughout the play. After all, who wouldn’t laugh at Jem being forced to abandon his pants after a nerve-wracking escapade through Boo Radley’s yard?

Yet Sorkin is also able to bring a necessary solemnity to the play; there is nothing comical about the standoff between a group of Ku Klux Klan members, Atticus, and the Finch children in the town jail. The trial of Tom Robinson is just as—perhaps even more so—heart-wrenching as it was in the book, and Bob Ewell is as spiteful and unlikeable a character as ever. Despite the sparseness of the play’s set, there is never any doubt that it is taking place in a jail or a courthouse—such is the convincing nature of the actors’ performances.

Although all the actors were undeniably fantastic, a few, in my opinion, stood out beyond the rest. Calpurnia (LisaGay Hamilton), the housekeeper of the Finches, is finally given a voice beyond that of simply a substitute mother figure in Sorkin’s adaptation. Here, she is fierce, protective, and most of all, angry—and the beauty of Sorkin’s adaptation is that it never tries to dismiss that anger as unjustified or disproportionate. Calpurnia is angry. She is angry at injustice, at inequality, and at the subtle racism that the African-American community faces every day—even at the hands of sympathetic white Southerners like the Finches. I found this reinterpretation of Calpurnia to be one of the highlights of the play; after all, in a story that centers primarily around inequality and injustice, why shouldn’t one of the most prominent African-American characters be able to express her own point of view?

On a completely different note, I was also enchanted by the performance of M. Emmet Walsh as Judge John Taylor. Judge Taylor is a comical figure—disaffected, a bit bumbling, but ultimately much smarter than he lets on—and Walsh was perfectly able to embody this nuanced character. Especially in the dramatic courthouse scenes, Walsh’s performance as Judge Taylor added some much-needed levity to the action.

Of course, this review cannot be in any way complete without praising the triumphant performance of Ed Harris as Atticus Finch. Sorkin’s Atticus, unlike Lee’s, is flawed. Sorkin reworked Atticus as a “character struggling to understand his morality rather than one who was absolutely certain of his morality,” Walsh stated in the talkback. Continuing, he explained, “I think very early on the idea that you should get into somebody else’s skin and crawl around in them may have sounded good. But it doesn’t quite make sense today that everybody is good and that if you just understand them it will be fine and racism will go away. Sometimes you have to be proactive.” Atticus, throughout the play, stressed understanding as the best way to counter racism—but in the end, Tom Robinson is still shot in the back, and racism in Maycomb persists. As a result, Sorkin’s Atticus is not the unwaveringly moral, always correct paragon of virtue that he is in Lee’s original novel. Sorkin’s Atticus struggles. Sorkin’s Atticus has internal conflicts, not just external conflicts, that he can find no easy way to solve. Sorkin’s Atticus is, in the end, simply a man—not a god. Yet Sorkin’s Atticus still remains immensely likable, and that is in large part due to the performance of Harris. Harris manages to bring every aspect of Atticus to life, no matter if he is arguing in the courthouse or sitting on the front porch. There are, in truth, no words to describe the magnificence of Harris’s performance.

Aaron Sorkin’s To Kill a Mockingbird, with Ed Harris in the role of Atticus Finch through April 19th, is a must-see play. If you only have the ability to witness one theatrical production this year, let it be this one. Unabashedly political yet compassionate to the end, it is a beauty.