The Haunting Horror That Is Homework

For too long, homework has plagued the world. It’s time to defeat this MLA-styled villain, once and for all.

Does the American education system have it all wrong when it comes to homework?

February 1, 2021

School pretty much dominates my life. Then there’s school for seven hours (pre-COVID). After school, I go home to do homework and study. By the time I’m three-quarters of the way done, I can barely keep my eyes open and I have to crawl into bed. I even have to wake up early to finish the homework I didn’t get to finish the night before. Then, I repeat. It seems normal enough to us. We’ve never known anything different. But trust me when I say that this is definitely not normal. I have friends who go to other schools. They are constantly hanging out, living their lives. I’m sick of not having one just because I go to THS. Everyone’s always telling me to go outside to get fresh air, to get more sleep. They have no idea how much I would love that to happen. But I know that if I get too lax, I’ll fall behind, or not finish some project. It’s a harrowing life to live, and I’ve had enough of it. Teachers and parents don’t realize how much stress this much work can put on a growing teenager. High School’s supposed to be the best years of your life, but I honestly can’t wait until I get to college and can have a normal schedule without Tenafly’s standards weighing me down. But what if all those hours of sitting at the computer, typing while our brains rotted… disappeared? What if, when the bell rang at three o’clock, the school day was actually over? We’d have the rest of the day to spend living our lives and being with those we love. Sounds like a dream, right? But what if it was an actual possibility?

Homework is rooted so deep in our culture that no one even stops to question it. For certain periods of time throughout history, though, people were much more receptive about the problems homework causes. ASCD.org (the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development) reports how, in 1900, Edward Bok, the editor of Ladies’ Home Journal, started the protest against the largely-accepted homework with a series of anti-homework articles. His aim? To abolish homework for all children under 15 and to establish a maximum of one hour of homework a night for older children. The movement for anti-homework was so strong by 1930 that the group formed the Society for the Abolition of Homework. American school districts nationwide voted to eliminate homework. For almost three decades following this, the school district policies of kindergarten through third grade had a near-universal condemnation of homework. The remaining homework was only assigned in small amounts. Bok had succeeded.

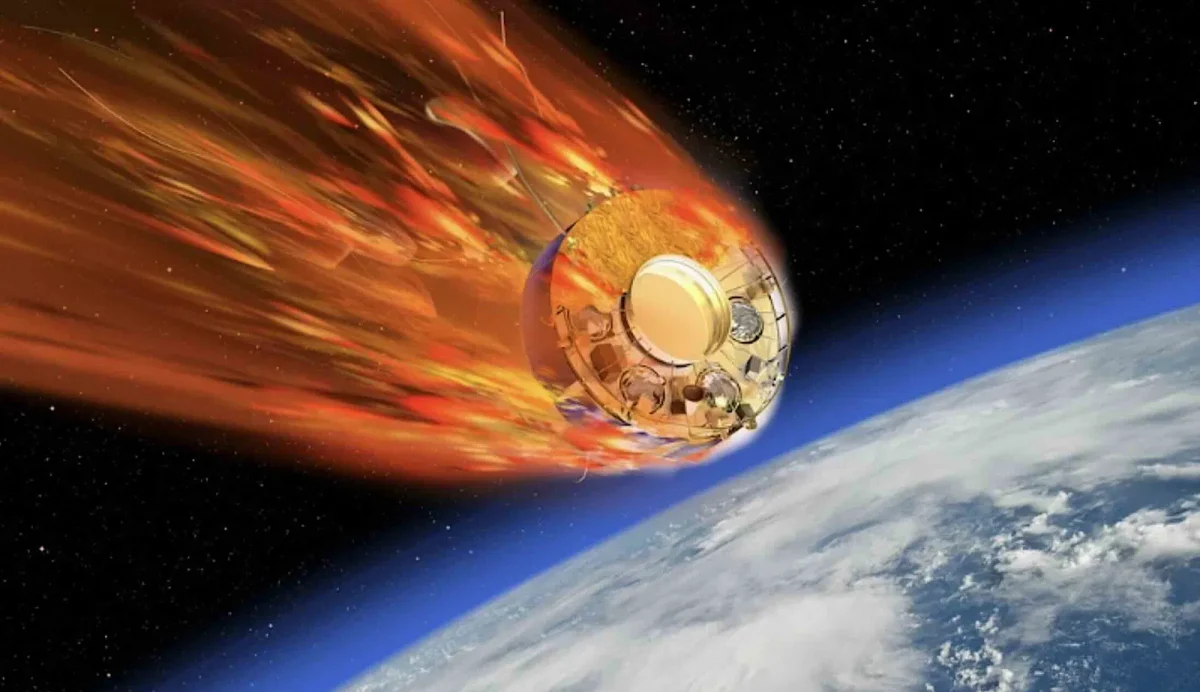

So what happened? Well, according to ASCD.org, in 1957, “the Soviet Union launched the Sputnik 1 satellite.” As the US became more and more obsessed with beating the Russians, the powers that be had an epiphany: the US was losing the Cold War because Russian children worked harder in school and were, therefore, smarter than American children. Too little homework was determined to be the reason for the worse American schooling. School officials, teachers, and parents were afraid that their children would not be prepared to compete in their future world. They saw homework as a solution. Within a few years, the public was in agreement that homework was needed again. As ASCD.org explains, many schools overturned the policies eliminating or limiting homework, which “had been established between 1900 and 1940.” And schools were back to square one. In a way it’s funny; we suffer today because parents from the late ’50s were overly-competitive, and wanted their kids to beat the Russians. No, never mind. Not funny.

In the late ’60s, the American Educational Research Association (AERA) and the National Education Association (NEA) defied public opinion, speaking out against excessive homework. “Whenever homework crowds out social experience, outdoor recreation, and creative activities, and whenever it usurps time that should be devoted to sleep,” AERA announced in 1968, “it is not meeting the basic needs of children and adolescents.”

It’s hard to not be just another face in the crowd of antisocial robots society churns out when we spend all our time alone under fluorescent lighting. We need contact with other human beings, physical activity, and a good eight hours of sleep a night, at least, to rest our overactive, overstimulated brains. Why do you think kids drink and do drugs when they know what it will do to them? It’s because they’d do anything for a boon, some respite from the tiring, painful ache that is living another meaningless day. And if that means messing themselves up, so be it.

According to ASCD.org, when the study A Nation at Risk came out in 1983 it became the government’s first major report trying to pin the problems of the economy on the schools and students. The report claimed that schools were getting worse and that “a movement for academic excellence was needed.” However, the researchers had no real proof. They simply wanted a scapegoat and children were helpless to defend themselves. And so, the National Commission on Excellence in Education (NCEE) was formed.

A Nation at Risk raised standards, starting the “intensification movement,” the idea that education is improved with more of it. This came in the form of longer school years, additional testing, and excess homework. In fact, A Nation at Risk actually called for “far more homework” for high school students. Guess we have the government to thank, after all.

It is shown in a University of Michigan (U of M) study that homework for 6-8 year-olds increased by over 50% from 1981-1997. As homework increased, stories about it showed up in the popular press. Before long, people, once again, grew critical of homework.

In the late 1990s, ASCD.org reports, many articles criticizing homework were published in educational journals. In 1998, AERA discussed homework in a symposium. That same year, research about homework by Harris Cooper got so much attention that the topic of homework entered the popular press and Cooper went on Oprah and Today to discuss his writings. In March of that year, Newsweek’s cover showed the articles “Does Your Child Need a Tutor?” and “Homework Doesn’t Help.” In January of 1999, Time magazine’s cover story was “The Homework That Ate My Family.” The story received significant media coverage, showing how homework interrupts family time and adds more stress to an already stress-filled life, especially for families with two working parents.

As ASCD.org states, in 2000, Piscataway, New Jersey schools implemented a homework policy limiting homework, discouraging weekend homework, and forbidding teachers from grading homework. Six years later, the story received national coverage and the school district received many requests from schools wanting a copy of the policy.

Canada and the UK were among the earliest countries to fight against homework, ASCD.org reports. The UK recommended banning elementary school homework in 2009, and Toronto abolished homework on holidays, on weekends, and in kindergarten in 2010. Around then, American elementary schools began limiting or eliminating homework. Homework concerns have come up in countries including Australia, Singapore, Japan, India, France, Greece, the Philippines, Ireland, and even China—long-considered the perfect example of educational achievement.

I understand that teachers have a certain amount of curriculum they need to teach in the year. However, most of the homework teachers assign is just busywork to drive home the ideas we learn in school. A lot of the time, it is totally unnecessary and does nothing more for me than take up my time. And though it’s unnecessary, I have to take the time, many hours in some cases, to complete the work or suffer the consequences. And in the classes with necessary homework, a lot of what we do at home could easily be done in class. I couldn’t hope to count the classes I’ve had reviewing the homework from the night before. Here’s a genius idea: why not just do the work in class? And if a student doesn’t understand something they learned in class, they can use self-discipline to review it until they do. The effort a student puts in would be reflected in tests, like always. That’s how you teach responsibility. By giving students a choice.

Although there is no evidence for it, many believe that homework, a literal requirement, promotes responsibility and discipline. However, when adults say responsibility, as ASCD.org says, they often mean obedience. Teachers want students to do what they want when they want them to do it. The whole point of high school is supposed to be preparing kids for college–for adulthood. Not instilling in us a constant fear of tripping up or forgetting something. So much so that we have it drilled into our brains to follow teacher instruction like mindless robots. Because that’s the ideal laborer, right? One who doesn’t talk back? One who knows how, but is too fearful or unsure to speak for herself? Right.

Students can be given responsibility in the classroom in ways other than homework. Ways that would actually work in teaching them responsibility. Teachers can involve them in decision-making, self-assessment, designing learning tasks, or managing classroom and school facilities. As ASCD.org reports, with regard to homework “children are rarely given responsibility for choosing how they wish to learn, how they might show what they have learned, or how they might schedule their time for homework.” Responsibility can only be attained by students taking power and ownership of their tasks. Anyway, 10 minutes of homework would work just as well in teaching responsibility as the many hours of homework we are assigned. Forty-two percent of students asked about homework in an Echo poll responded that they spent 3-4 hours on homework a night. In reality, all of that time is spent on basically meaningless activities. Taking the initiative to do even a simple worksheet when not required could be all it takes to teach a developing child responsibility.

Some say that homework teaches time management. But I agree with ASCD.org when I say that time management does not mean working instead of playing. Anyway, homework doesn’t teach time management if parents have to convince their kids to do it and if the kids who do it only do so for fear of punishment. And long-term projects requiring scheduled planning are better for teaching time management than daily assignments.

As ASCD.org states, it is not a teacher’s obligation to continue teaching students once they leave school. Teachers don’t “have the right to control children’s lives outside of school.” Teachers may say that homework is better than TV or video games and that it keeps kids out of trouble, but it’s not up to them to make decisions for their students. That’s the parents’ responsibility, and they should be trusted to do their jobs as parents. It is not the teachers’ jobs to be the morality police of their students’ personal lives.

People who are pro-homework believe intellectual development takes precedence over social, emotional, and physical development. However, this is false. According to ASCD.org, “physical, emotional, and social activities are as necessary as intellectual activity… in well-rounded children.”

Many believe that a tough school gives homework, disregarding the assignments’ length or type. In the 1800s, people believed that the mind was a muscle to be trained, and so it only got stronger with more work. It’s sad that with all of our modern developments, people still think this. As ASCD.org explains, they think that “[i]f some homework is good for children, then more homework must be even better.” Because too much of a good thing could never be a bad thing. Yeah, right.

Sorry to go against popular belief here, but a heavy workload is not automatically rigorous, just time-consuming. The assignments could be busy work with no educational value. ASCD.org explains how difficulty is often incorrectly connected to the amount of assigned work, not with its actual difficulty level. More time does not equal more learning. This “ignores the quality of work and the level of learning.”

Many incorrectly assume that homework is inherently good. According to ASCD.org, people believe that good teachers give homework and an easy teacher is defined by one who doesn’t. Children who complete homework are called “compliant and hardworking,” while children who don’t are dubbed lazy and noncompliant. And don’t pretend all you, teachers, don’t label your students in your mind. But how is it fair to determine who a person is—their worth—by whether or not they hand in some meaningless assignment? What if a student has private issues going on at home that mentally or physically prevent them from doing the work? Or what if a student has a single mother who he has to help during the day, leaving no time for Algebra? The possibilities are endless, yet defenseless in the face of the cruel abomination that is homework.

I know that Tenafly does not deserve all the blame here. No, the district didn’t start this meaningless, ridiculous tradition. The world did. Society did. It’s taken me a while, but I’ve come to realize that society is often wrong.

It’s only right to correct it.