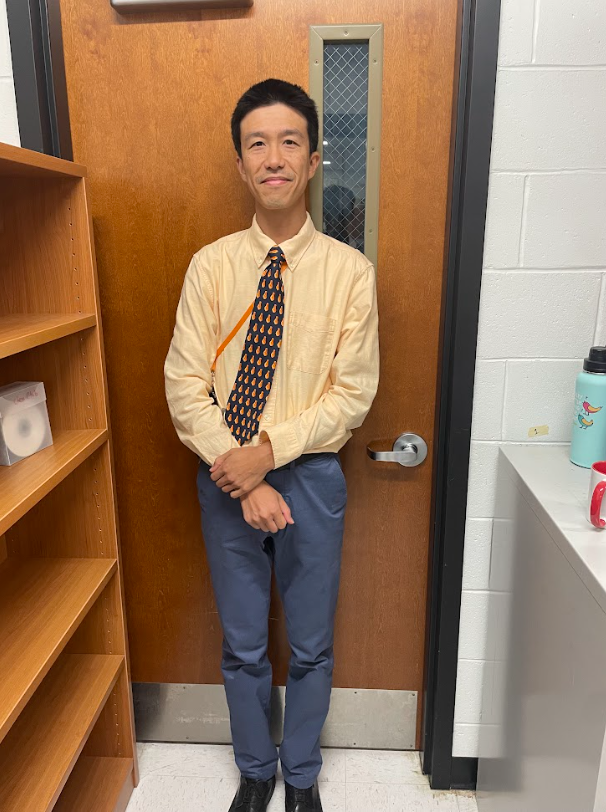

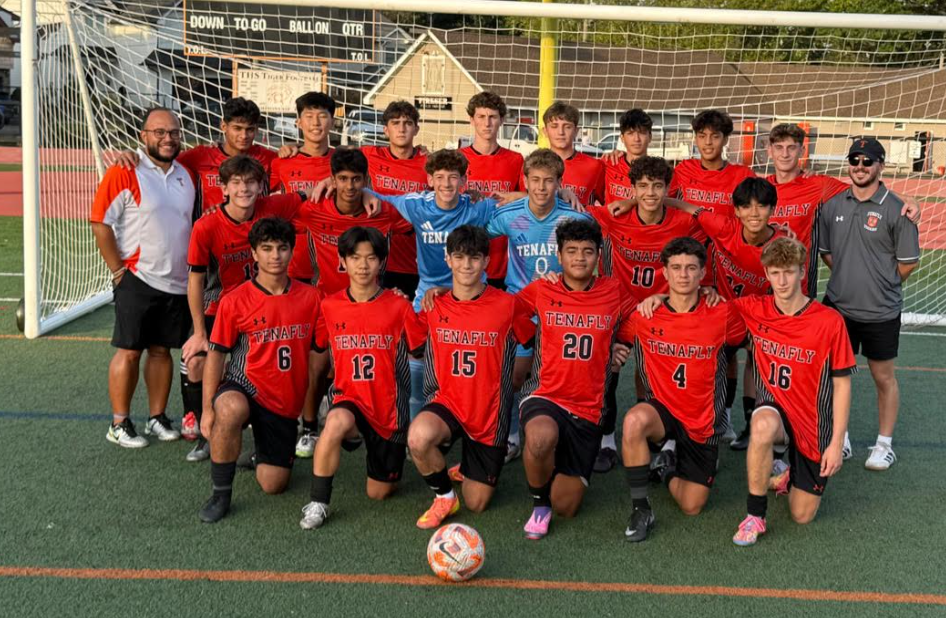

If you have taken World Literature II or AP Language and Composition here at Tenafly High School, you may have already met Ms. Lucine Kinoian. She has been teaching at THS for three years and was previously at the middle school for six. And if you have had her and decided to explore her Tenafly website, as I did, you may have come across a TEDTalk she gave titled “An Armenian Genocide Survivor’s Story.” One defining feature of Ms. Kinoian’s personal identity is her ancestry, as well as the stories that have been passed down to her from these ancestors, stories that describe the lives of Armenian genocide survivors.

Kinoian has been taught about her culture from a very young age. Her “family would take [her] to church, cultural events, and Armenian social events in the community.” And once she got older, she was introduced to the story of her great-grandmother, Anna, who was only 11 years old when Ottoman Turkish officials started rounding up Armenian people, marking the beginning of the violence against them. At 11 years old, Anna had to watch “as her father, uncles, and beloved cousins were shot to death.” Shortly after, Anna and her remaining family, her mother and sisters, began a march—more specifically, a death march across the Syrian desert. This march was an unyielding and cruel ordeal, with scarce food and water, and women giving up mere days after it began. The Turks did not intend for there to be any survivors of these month-long marches, and people starved perished of dehydration, and those who dropped out were left to die. One morning, while attempting to gather water from a nearby well, Anna was kidnapped. She fruitlessly cried out to her mother and sisters, but her abductor ended up prevailing. Anna became one of her abductor’s several wives and was forced to bear two children. Luckily, after a few years, she was able to escape, but this did not mean that her life got instantly better, it simply meant she was able to find safety and refuge. Her life would still be riddled with adversity. Anna escaped to France and was reunited with her mother and sisters. There she also met her future husband and he brought her to America where they started their own family. After moving, her two daughters got into contact with her, through letters, and after coming to realize that her abductor had died, “for the first time in nearly 50 years, she felt it was safe to go back and to go find these girls.” Anna had borne witness to massacres and had suffered both rape and abduction. It took her 50 years to speak about it, to share her experiences with her family and her children. And Anna’s story isn’t the only one she grew up hearing about.

“I have stories from all four of my grandparents [and] stories from all of their parents,” Kinoian said. Her cultural background has impacted her personal identity immensely, and she is very involved with Armenian organizations.

“It’s because my family raised me, just as my grandmother’s family raised her, to be proud of our survival and to know the truth of the struggles our ancestors faced,” she said.

She can recall one story of a relative having to hide under a pile of dead bodies, to escape the guards who were searching for him. “These are disgusting, heart-wrenching stories to hear, let alone to think about,” she said. “My reaction to [first hearing] these stories was the same as it is now: How could anyone be so cruel to another human? How could anyone so blindly hate the innocent?”

These stories and the experience of hearing them are a huge part of Kinoian’s passion for bringing awareness to Armenian issues and injustices happening around the world. As hard as talking about the devastating stories is, they help to shape her identity.

“It’s all the more reason why it is very important for me to continue practicing my culture, sharing my heritage, and taking pride [in saying] ‘Yes, I am Armenian.’”

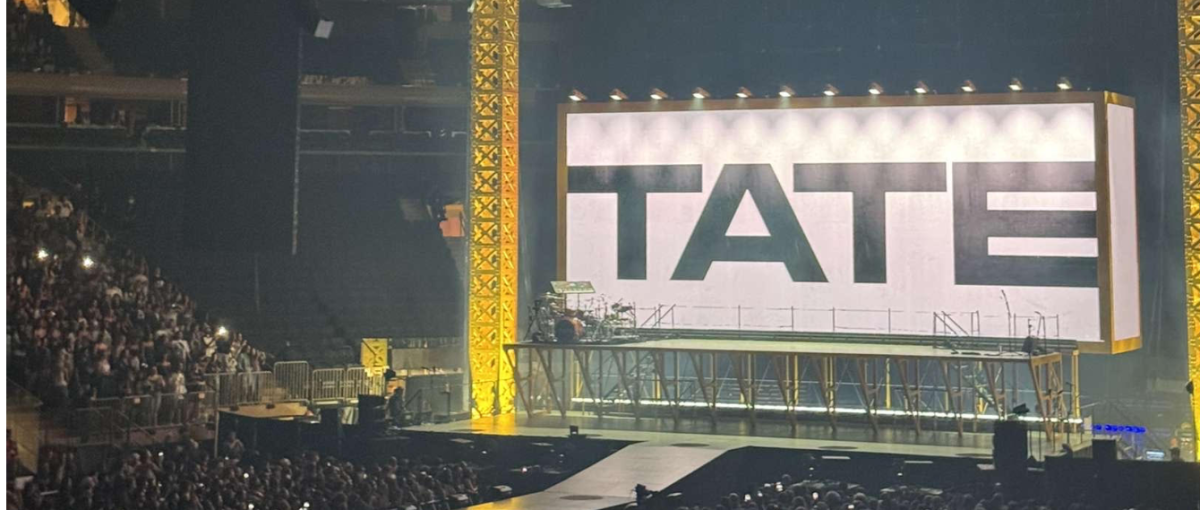

Circling back to her TEDTalk, Kinoian was able to share Anna’s experiences on a huge scale. The way that she was asked to do the TEDTalk was actually a funny story. She was first approached by Bergen Community College and an organization called Facing History and Ourselves to do the talk because she was attending a workshop on teaching genocide in secondary education curriculum. As soon as she walked in the doors, she was met with the words, “Oh, you must be Armenian.” The event hosts told her that they were hosting a TED event in three week’s time and asked, “Do you want to participate? You must have a genocide story.” And although it was nerve-wracking to even fathom standing up on stage, speaking in front of so many people about such a sensitive subject, she knew that she couldn’t say no, that she had to do this. She simply replied with, “Which story do you want to hear?” and ended up going with Anna’s story due to its obvious impact and gravity.

Every now and then she will log onto YouTube and watch the views go up. The recognition is exciting to her, but what excites her more is all the hate comments. To Kinoian, it shows that “all the genocide deniers are watching. They might not accept history, they might be living in a bubble—in many ways—but “They’re watching and learning.”

However, the stories of her relatives aren’t the sole factor in Kinoian’s devotion to raising awareness; the irony that she witnesses, as a third-generation survivor, is another. The Armenian Genocide is largely recognized as the “Forgotten Genocide,” and it’s so ironic and upsetting to Kinoian that it’s referred to as such, “because history shows that it’s not forgotten.” The Armenian Genocide has been recognized in many instances. Hitler referenced the killing of the Armenian people before his invasion of Poland in 1939, recognizing how Turkish officials were never held accountable for the crimes they committed.

“It’s estimated that 1.5 million Armenians were forced from these ancestral lands and killed. If you are looking to annihilate a group of people, it’s not surprising to see why Hitler would consider what the Turks did to remove the Armenian population a rather successful mission.” Kinoian said.

And to delve even further into the ironic title that the Armenian Genocide holds, the Armenian Genocide has helped the world recognize what a genocide is. Before the 1944 case study conducted by Raphael Lemkin, a Polish-Jewish lawyer and activist, which linked the Holocaust and the Armenian Genocide, people had “used words like ‘massacres’ and ‘barbarities’ and ‘atrocities.’ It was not until this case study that the word “genocide” was brought to existence.

And the most “frustrating and gut-wrenching part” to Kinoian is that “Turkey actively denies the crimes of [its] past.” Kinoian has had the chance to visit Germany and see how citizens are educated about their country’s wrongdoings, and it is painful for her to see the contrast between the two countries’ responses.

“Turkey, over the past 108 years, [has] continued an active agenda of denying the genocide, [and] as a result, in modern-day—in live time, actually—there are Armenians facing the threat of genocide yet again.” Since the Soviet Union’s collapse, the Turkish-backed Azerbaijani government, with Turkish support, has sought to expel Armenian communities from Artsakh Nagorno-Karabakh, their ancestral lands. Conflict erupted in 2020, resulting in Armenians losing ancient church grounds, monasteries, and historical monuments. They endured the shelling of their homes and cities, having to shelter children and close schools, with the crisis reaching a breaking point on September 25, 2023, triggering a mass exodus of over 100,000 Armenians, with these people having to flee for their lives due to dwindling resources and relentless threats.

To Kinoian, “It’s one thing to kill a person in times of war or as an act of self-defense, but it’s another thing entirely to seek out someone with less power with the intention of destroying and causing harm to them and all those like them.” She is extremely aware of the fact that she exists due to the utter strength and endurance of her relatives, and she “holds this to be at the very core of who [she] is as a person,” which impacts how she hopes to bring awareness to the issues Armenian people face. She “hopes [that] we live in a world… where people recognize what happened to the Armenians, even if the country of Turkey won’t acknowledge their own history.” She hopes that people now, can hear stories like those of her family and be able to empathize with the struggles that they went through and the ones that people face currently.

“I now live in America but that’s only because of the unimaginable experiences [my family] endured that brought them to new countries and cities, far removed from the lands of their parents and their grandparents. I do whatever I can as an American of Armenian heritage to keep their history alive and, in turn, keep my culture alive. Armenian culture is rich with language, music and dance, food and hospitality, religion and art, and I immerse myself in it all by staying active in local Armenian community events. And this personal history has shaped me to be empathetic to injustices against all people, from all cultures and backgrounds. I believe it is important to be a voice for the oppressed—a voice for the otherwise unheard so that histories are not forgotten.”