When climate change is referred to, snow crabs aren’t typically the first thing that comes to mind. However, for years, scientists have been unable to explain the drastic drop in snow crab populations as they reached a record low in 2021, with ten billion snow crabs gone in just three years. Until now.

Snow crabs are cold-blooded crustaceans that are native to the eastern Bering Sea off the coast of Alaska, where they live on the shallow areas of the ocean floor. These crabs thrive in cold water, and rely on the cold-water pools that are created as winter sea ice melts, causing this frigid meltwater to settle on the seafloor. In relation to humans, these crabs are a well known delicacy and closely tied to the economy as they are often caught by Alaskan fishermen, who sell them to numerous markets, drawing in mass amounts of revenue for Alaska fisheries, with numbers reaching $150 million annually, according to ScienceNews. However, in recent years, this number has fallen by 84% as snow crabs become harder to find. This caught the attention of many scientists, and through experiments and data collection, they came to the conclusion that the extreme drop in snow crab population came from higher water temperatures and a dense crab population.

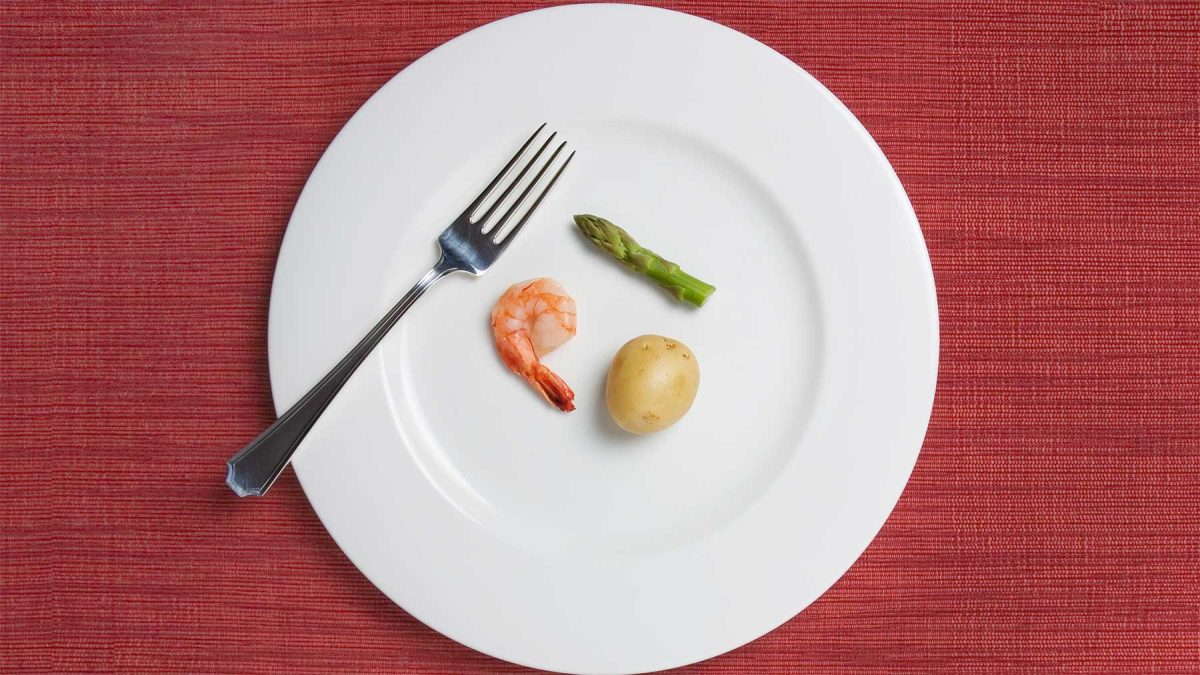

Climate change has been a continuous battle humans have faced, but little attention is given to how it has affected cold-blooded animals. In warmer temperatures, to accommodate this change, cold-blooded animals tend to have a faster metabolism, which can lead to starvation if there isn’t enough food around to support them.

According to the report by Jude Coleman in ScienceNews, for the snow crabs, scientists have found that through marine heat waves, less ice was able to develop, leading to the cold-water pools never forming. These cold-water pools are typically around 36 degrees Fahrenheit, and without this safe haven, the crabs lose the cold water that they thrive in. However, scientist Cody Szuwalski and her colleagues who studied this case did not believe that it was directly a change in temperature that led to the ten million snow crab deaths because, through experiments, they found that snow crabs can live in temperatures up to 53 degrees Fahrenheit. Instead, Szuwalski and her colleagues considered starvation to be a key factor. Back in 2018, before the marine heat wave, the snow crab population was building, but also in a smaller area than usual. Szuwalski could not offer an explanation as to why the population was condensing into a smaller space, but the effects of this most likely led to the population’s downfall. As the marine heat wave swept through, the snow crabs’ metabolism grew faster, leading to a higher demand for food. However, with a smaller foraging area and higher competition, it likely led to many snow crabs starving to death.

As climate change continues to become a larger issue in today’s world, the effect of marine heat waves will soon expand past snow crabs and to other marine species. This will change ecosystems and have a larger impact on the world’s markets and food sources. According to UNCTAD, about three billion people rely on the ocean for food and income, making it extremely important to place more attention on these marine sea animals and their ecosystems.