The imposing hippopotamus is one of the largest land mammals on Earth. These majestic creatures are native to subsaharan Africa. So, how’d they end up in the rivers of South America, half a world away? The story starts three decades ago at Hacienda Nápoles, the former estate of the infamous Colombian druglord Pablo Escobar.

Escobar, once the head of the notorious Medellín cartel, lived at Hacienda Nápoles, an enormous estate located between the Colombian cities Medellín and Bogotá. The property was comprised of not only the main house but also various other luxuries, such as an entire zoo filled with exotic animals imported from all around the globe, including ostriches, elephants, giraffes, and, of course, hippos.

After Escobar was shot and killed in a standoff with the Colombian police in 1993, most of the animals previously housed at Hacienda Nápoles’s private menagerie were relocated to various zoos across South America. The hippos, however, were deemed too difficult to capture and transport, and were thus left unattended to on the estate. There were originally only four hippos roaming the grounds of Hacienda Nápoles at the time of Escobar’s death, but in only a few years, they spread into the nearby Magdalena River and multiplied in number. As of April 2023, the population had grown to 181-215 hippos strong, as estimated by Colombia’s Ministry of Environment. The escapee hippos have since become known as “cocaine hippos,” after their deceased owner’s reputation as a cartel kingpin.

Of course, the presence of these cocaine hippos isn’t without a fair share of issues. Hippos are notoriously territorial and aggressive and cause around 500 human deaths every year, according to USA Today. In Colombia, more and more concerns have been raised about the cocaine hippos wandering too close for comfort to fishing villages along the Magdalena River. There have been multiple recorded instances of the hippos attacking locals and damaging livestock and property, but no cases have been fatal so far.

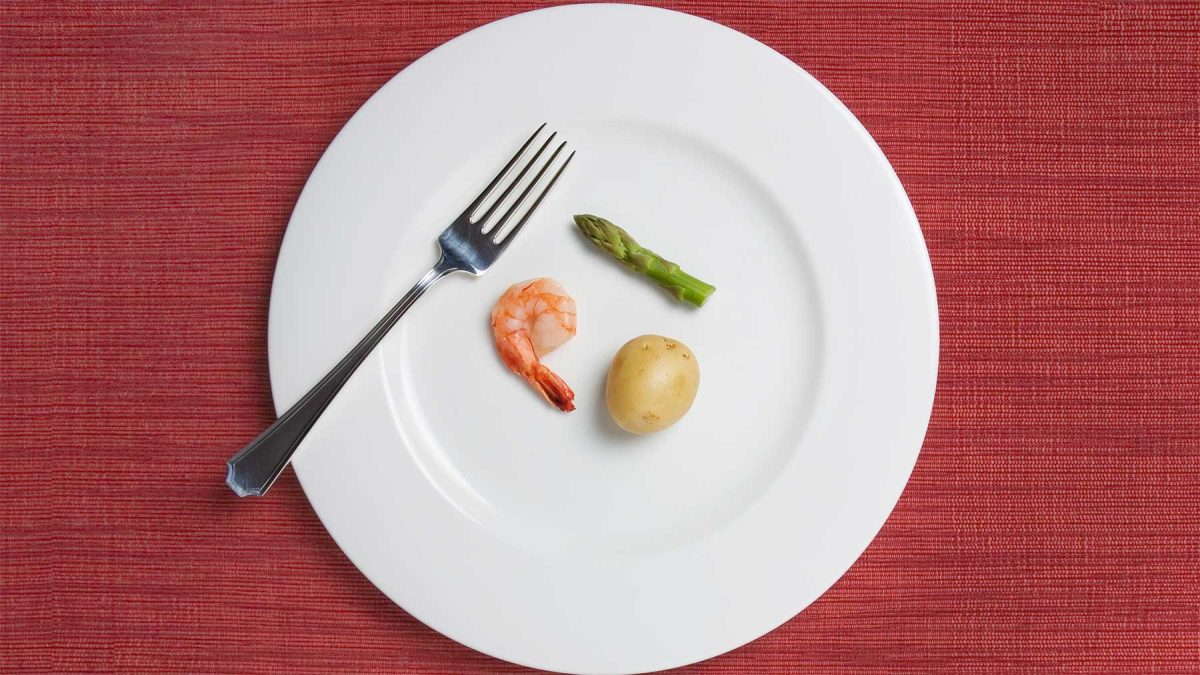

Impact on humans aside, the hippos are also causing a plethora of problems for the local ecosystems. Hippos can excrete large amounts of nutrients into water bodies through feces, increasing the turbidity of the water and altering the composition. This could negatively affect fish populations, causing ripple effects across the food web and putting other native species at risk. The cocaine hippos have already begun to outcompete several native species such as manatees, river otters, and capybaras; when you’re a walking tank with knives for teeth, there’s very little that can stand in your way. As hippos have fewer limiting factors such as dry seasons and no natural predators in South America, their population in Colombia will continue to grow exponentially in the coming years if humans don’t step in.

But despite all the adverse effects on the environment that the growth of the Colombian hippo population may present, many don’t want the hippos to go. Previous attempts by the Colombian government at culling the population have resulted in widespread public outrage over the ethics of the operation, especially from animal rights activist groups who have advocated against the killing of the hippos. As covered by the LA Times in 2009, after the culling of one male hippo named Pepe, who had been posing a danger to locals, the government was faced with immense backlash after a picture of its carcass was leaked online.

Others take a very different perspective to how the cocaine hippos should be dealt with. “Why would you want to be propagating a potentially alien invasive species that’s very dangerous?” Michael Knight, a South African ecologist, wrote on The Yale Politic. “You have to ask from a biodiversity conservation perspective, what objective is this fulfilling? Nothing more than a zoo.”

In any case, there has been too much pushback against the option of culling the hippo population, and the Colombian government has recently updated its decision: As of November 2023, the government now aims to sterilize at least 40 hippos a year. This won’t be an easy process by any means. Hippos are big, heavy, and very difficult to sedate for long enough periods of time to be sterilized. It’s not easy to move around an animal that’s 3-4 tons, especially when that animal is equipped with tusks that can reach over a foot long and has an even bigger temper to match. Additionally, the process of sterilization itself isn’t exactly cheap. According to the New York Times, Colombian officials currently estimate the cost per sterilization to be around 40 million pesos, or $10,000. With an estimated number of over 200 hippos roaming the nation now, authorities could well be looking at a cost totaling millions upon millions of dollars for the successful sterilization of the entire male hippo population.

Nonetheless, as of now, sterilization seems to be the best alternative to a complete extermination of the population.