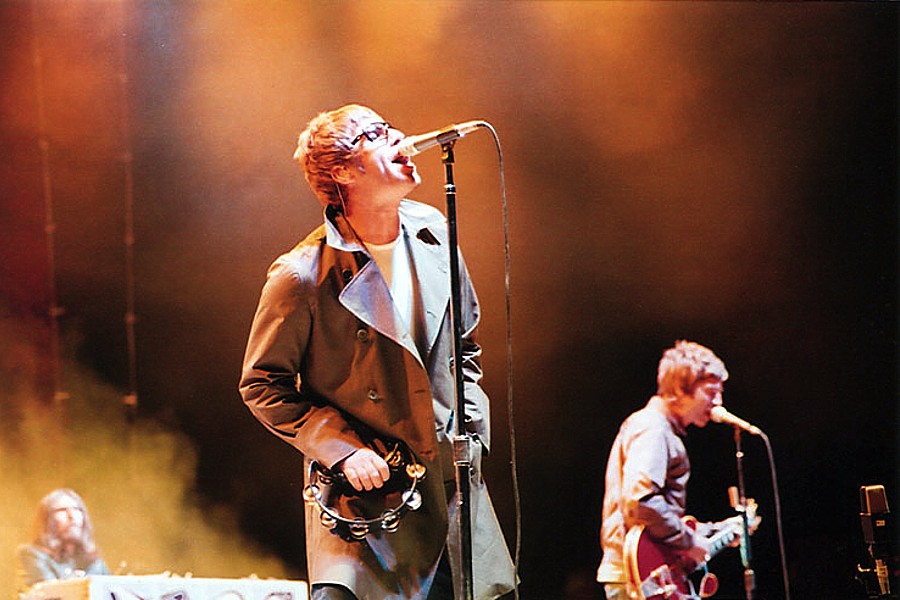

Somewhere deep in the history of the 20th century, at the place where nostalgia meets bitterness, a swanky 1978 Ford Thunderbird (pale blue, with red shag carpet) overlooks a small town from its perch on a hill. Amidst the golden dust of retrospection, if you listen closely enough, you just might make out, leaking through the stereo speaker system, the mighty sounds of Greta Van Fleet. The four-piece Michigan hard rock outfit, composed of three brothers and a friend, have managed to become one of the most polarizing bands in the world. Whether you love them or hate them, however, your reasoning is probably the same: they sound just like Led Zeppelin. And I don’t mean in the way that Oasis apparently sounded “just” like the Beatles, or Stone Temple Pilots were said to have sounded “just” like Pearl Jam. What I mean to say is that these guys are one impassioned moan or double-bass drum roll away from being a full-on cover band.

There’s something cannibalistic about the way that Greta Van Fleet recycles the trappings of bygone cultural movements and turns them from something that was genuinely subversive during its time into an appeal to nostalgia. Listening to a Greta Van Fleet song, you might get a similar feeling to hearing “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” playing at a Trump rally, realizing, only after a few seconds’ time, that these things, at least at one point, meant something fundamentally different. Implied somewhere in their all-too sincere pastiche of the 1970s is a fundamentally pessimistic premise: the best rock music, the best culture, all of the exciting and inspiring things that could happen or ever will, have happened already in our parents’ generation and in their parents’ generation, and all that is left for us pitiful screen-gazing Zoomers is to try to relive it as best we can. And if you think that’s reading too profoundly into a harmless nostalgia act, I encourage you to take an honest look at the state of modern popular culture. Pervading everything is the deep sense that we’ve come to a crossroads as a culture. The culture of young people in America is no longer just ironic, it’s post-ironic, meta-ironic, an ironic comment on irony. The whole cultural progress of the past seventy years seems to have absorbed itself into one massive convoluted, excruciatingly self-referential web. Rather than move forward, American popular culture seems to be feeding on itself, playing off of nostalgia to generate more content. This brings me back to Greta Van Fleet.

Greta Van Fleet’s fetishization of ’70s rock culture is indicative of more than just a desire to get rich off of copping Jimmy Page’s chops; it’s the kind of thing that happens when you no longer have enough faith in your own story to even try and tell it.

All of this then poses the question: where do we go from here? What are we to do, when the most forward thinking thing is to go backwards? Is there any point in moving forward at all, or backwards, or in any direction for that matter? The very question leaves you sort of paralyzed in time.

I don’t know the answer to that question, but I do know this: the world that my generation is growing up in is fundamentally different from that of our parents and their parents. The basic reality that we refer to on a day-to-day basis has completely changed. Greta Van Fleet wants to pretend that this is not so. I think that’s a bad idea. I think, in order to really grasp something sincere, we need to step into the thicket of modern life and engage with it in all its complexities, half-truths, and ambiguities. And maybe, in doing so, we can pull out a nugget of genuine truth.