Although they are one of the most well-known waterfowl, ducks are also often overlooked. In appreciation of these silly unique creatures, here are five distinguished ducks that you might or might not have heard of.

Mallard

Starting off with the blueprint—the mallard. This is the “standard” duck, if it can be said that there is one. Mallards can be found in North America and Eurasia, and are the ancestors of most domestic ducks. As with most birds, males are noticeably more flamboyant, and females don a comparatively unspectacular brownish plumage.

When migrating, mallards have been recorded flying at speeds of up to 55 mph, setting them comfortably around the middle of the average flight speed range of most waterfowl (40-60 mph).

As mallards often inhabit urban areas, It’s not uncommon to see flocks scrambling for free handouts at a park. But a word of advice to the charitable bird-lover: bread is not the best thing to give out, as it is almost void of nutritional value for ducks, and may lead to malnutrition and sickness in the long run if over-consumed, which is unfortunately a very real possibility for fat ducks in parks who are accustomed to gorging themselves on grub from humans and eat nothing else. Consider frozen peas or leafy greens next time you run into park ducks instead.

Harlequin duck

Our next feature is the hardy harlequin duck, a small duck that primarily occupies coastal areas along the northern Pacific and Atlantic shores of North America, as well as eastern Russia. Cold, turbulent waters dominate its areas of activity; it’s safe to say that where there are fast-flowing rapids, rough surf, and whitewater, you might find a happy harlequin swimming in the waters.

The harlequin gets its name from Harlequin from Commedia dell’arte, as its unique coloration resembles the showy, boldly-dressed character. They have a number of other monikers as well, including “lords and ladies,” “painted duck,” “totem pole duck,” and more.

Due to their habit of diving for food such as crustaceans or small fish, Harlequins’ feathers are great for insulation and buoyancy. Harlequins will also forage on exposed rocky shores. According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, they “suffer more broken bones than any other species,” which is likely caused by their lifestyle of tumbling around in wild waters.

Ruddy Duck

Also known as oxyura jamaicensis, the ruddy duck is not to be confused with its various other blue-billed, stiff-tailed cousins, who all reside on different continents. Of all the ducks in the Oxyura genus, the ruddy duck is the only one whose natural range includes North America, though they’re considered invasive pests outside of the Americas due to their ability to hybridize with local native species. Males sport vibrant blue bills and perform a courting display known as “bubbling” in order to attract mates, done by drumming the bill on the chest with sufficient strength to produce bubbles on the water’s surface.

The physiology of the ruddy duck is often described as “chunky” and “compact.” And while those tags are applicable to the vast majority of ducks, the ruddy duck is particularly prone to insulting remarks from human commentators. A description from a 1926 account describes the ruddy duck as follows: “Its intimate habits, its stupidity, its curious nesting customs and ludicrous courtship performance place it in a niche by itself…. Everything about this bird is interesting to the naturalist, but almost nothing about it is interesting to the sportsman.”

Sounds like that guy had something personal against these ducks. But if that quote is the case, I may be more of a naturalist, because I think ruddy ducks are pretty interesting.

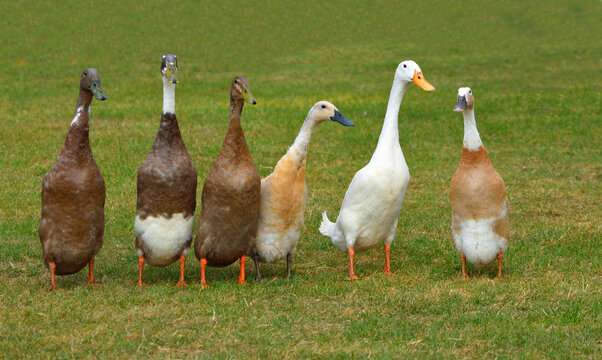

Indian Runner Duck

This one will really shake up our silhouette variety. Indian runner ducks stand and move in a distinctly upright fashion, as due to how far back their legs are positioned on their bodies, they are unable to walk in the frolicky waddle so characteristic of other ducks. Its wings are too small for flight, so it runs instead. It can flap its miniscule wings all it wants and may glide a few feet if a good wind is caught, but it cannot fly.

English naturalist Alfred Wallace noted in 1856 upon seeing an Indian runner duck that they “walk erect like penguins.” Since then, this unique duck’s unusual posture has earned it the nickname “Bowling Pin Duck.”

The Indian Runner Duck’s name is actually a bit misleading, as there’s no evidence of the breed having originated in India. Records indicate instead that they were bred on Indonesian islands, with the mallard being their ancestor. Runners became well-received in Europe and the Americas in the late 19th century after being introduced there for their prolific egg-laying performance, with hens laying over 200 eggs a year. The popularization of the breed was also thanks to a pamphlet called The Indian Runner: its History and Description, published by John Donald of Wigton in the late 1890s.

Call Duck

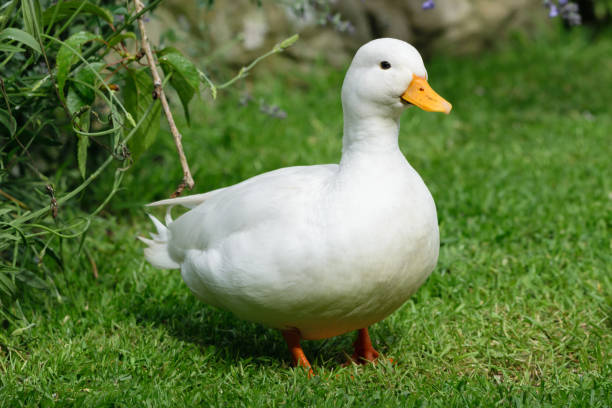

Here is another duck we may be more familiar with. Named for its higher-pitched quack, the call duck is notoriously vocal and chatty. This breed originated in the 17th century Netherlands as a domestic “decoy” for hunters to catch wild waterfowl, as their calls would attract wild ducks to their position, where a funnel trap would be waiting.

Call ducks are the smallest duck breed, and weigh on average 500-1000g. Nowadays, due to their diminutive size and lack of productivity in egg-laying, they serve no use as farm birds and are almost exclusively kept for exhibition purposes or as pets. Many favor them for their sociable nature, polite expression, and round frame.

In terms of exhibition, while standards for show call ducks change over time, show-quality call ducks are generally accepted as having rounder heads and shorter bills. They also come in a variety of colors and patterns: the capped Fawn, the pied Magpie, and the classy Bib, just to name a few.

Although these are the 5 distinguished ducks for this article, there are currently over 130 recognized species of ducks in the world, leaving many more to be considered. I hope you’ve learned a bit more about our feathered friends today, and I look forward to writing more about our avian associates on Linda’s Nature Nook.