The proposed construction of a natural gas-fired backup power plant in Newark’s Ironbound neighborhood has ignited a fierce debate, highlighting the tension between infrastructure resilience and environmental justice.

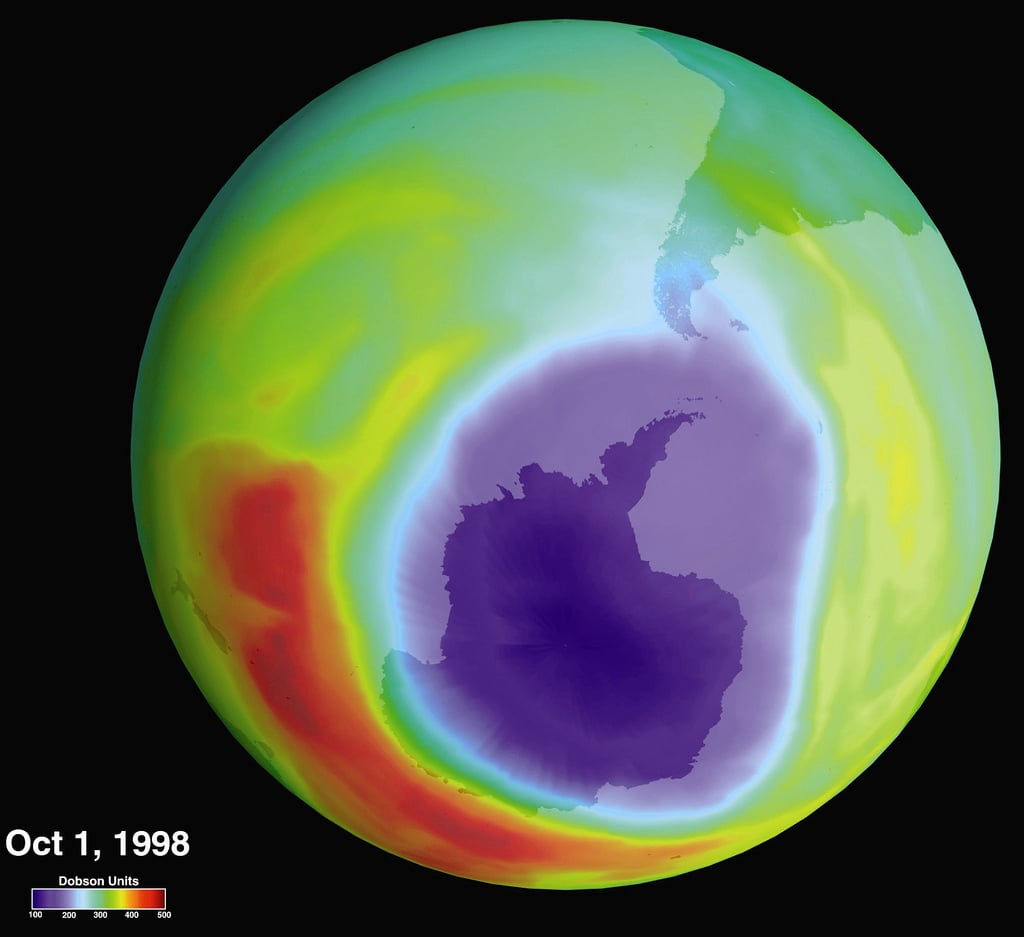

Officials claim that the upcoming project is a necessary means of protection to prevent catastrophes similar to the sewage spill following the 2012 superstorm, Sandy, during which the failure of the Newark electrical power grid subsequently shut off the Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission wastewater treatment plant. This caused 840 million gallons of untreated sewage to flow into local waterways, including the vital Passaic River and Newark Bay. The proposed power plant aims to prevent a repeat of this disaster by providing a dedicated backup power source that would keep the wastewater treatment facility operational during future outages, according to The Bergen Record.

However, many community members argue that this $180 million project would simply exacerbate the climate issues in the already over-polluted neighborhood, expressing concerns for the greenhouse gases that could be released from an additional fossil fuel plant. They protest that the Ironbound neighborhood’s proximity to industrial sites, highways, and even the Newark International Airport has made for more than enough pollution—a claim supported by the fact that one in every four children raised in Newark is diagnosed with asthma, as proven in a study conducted by Rutgers Health. Senate Majority Leader Teresa Ruiz criticizes the plant in a similar way, arguing that “it disregards the well-being of Newark residents who have long borne the brunt of toxic air pollution and negative health outcomes from nearby power plants built in their communities to shield more affluent areas from its harmful effects,” as reported by New Jersey Globe.

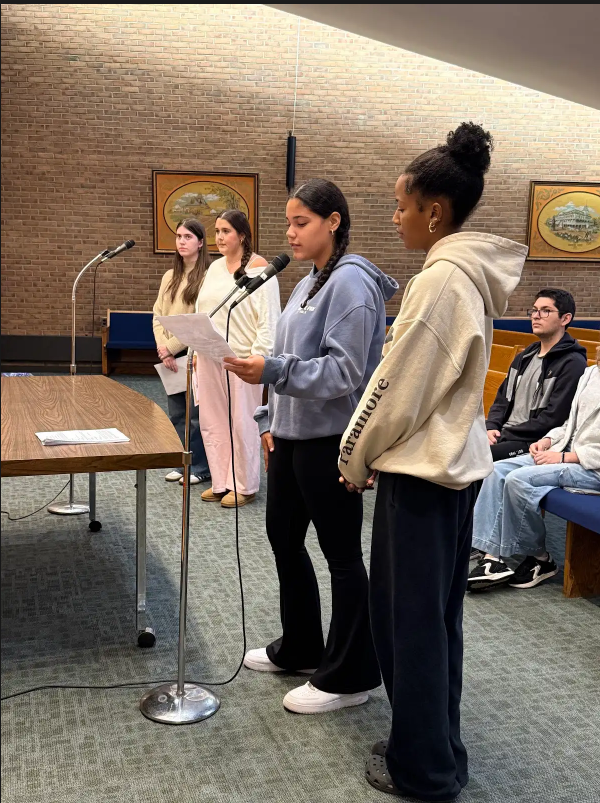

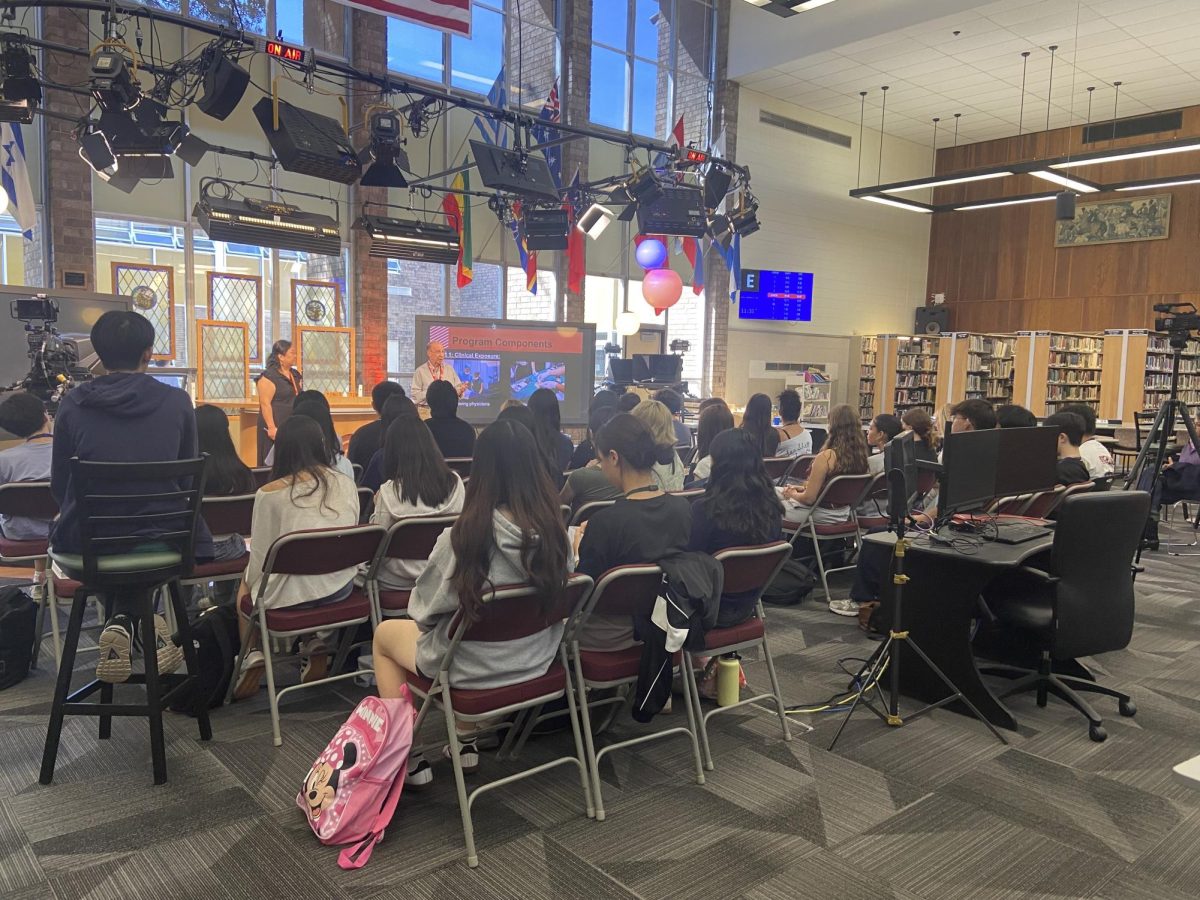

Opposers have not been shy to showcase their opinions. In a rally held on March 13, speakers urged for the rejection of the plan that was granted a permit by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection in the month prior. More than thirty worried residents and advocates, much like the policy analyst Chloe Desir—who was also a guest presenter at the rally—stood their ground.

“We have endured enough: the rancid smells, the soot, the toxic emissions, the never-ending truck traffic,” Desir announced, according to NJ Spotlight News. “This is what environmental racism looks like,” referencing the term that describes the disproportionate impact of environmental hazards on marginalized communities, which was first coined by Benjamin Chavis during the 1982 North Carolinian protests against the formation of a government-funded toxic chemical landfill.

Although one final air permit is still needed as a prerequisite to the beginning of construction, the site is expected to break ground later this year.