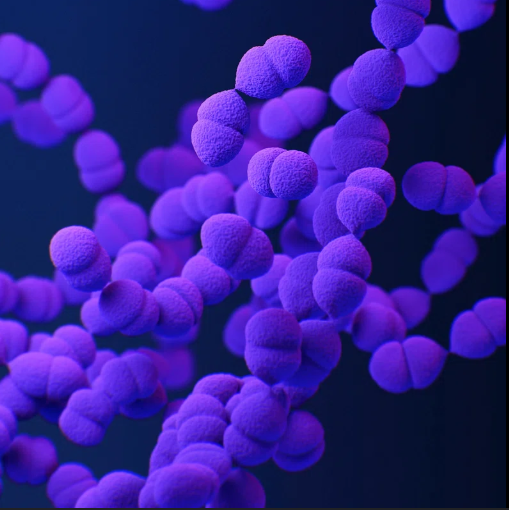

Each year, around 12,000 Americans die from one of the most devastating cancers in modern medicine: multiple myeloma. Long considered incurable, the disease has long been studied and a breakthrough may finally offer sufferers a reason to hope.

According to the American Cancer Society, approximately 36,000 Americans are expected to be diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2025, and more than a third of them are likely to die from it. The disease attacks plasma cells in the bone marrow, multiplying uncontrollably and crowding out healthy cells. As it spreads, it begins to erode bones from the inside. X-rays often reveal skeletons riddled with holes, as if they’d been punched through or gnawed away. Some patients lose as much as six inches in height, according to The New York Times.

“Advanced myeloma is a horrible, horrible death,” Dr. Carl June, of the University of Pennsylvania, said. “It’s a death sentence.” Over the years, countless treatments have been developed, but they rarely last. Patients often grow resistant to each new drug, leaving doctors with no more options and families with no more time.

That may be starting to change. A new form of immunotherapy called CAR-T is showing striking promise. The process involves removing a patient’s white blood cells, genetically reprogramming them to detect and destroy cancer cells, and infusing them back into the body, according to The Times. It’s not a new concept: CAR-T has been used successfully against other blood cancers like leukemia—but its effectiveness against multiple myeloma had long been in question.

Then came a surprising contender: Legend Biotech, a Chinese biotech company that developed a new version of CAR-T tailored to myeloma. Initially met with skepticism by American researchers, Legend’s therapy eventually caught the eye of pharmaceutical giant Johnson & Johnson. The two companies joined forces to test the treatment on American patients who had failed at least one standard line of care, meaning they had already undergone one treatment method.

To the surprise of researchers, the treatment worked, even in patients whose immune systems were deeply worn down from years of treatment. “It seemed almost too good to be true,” Anne Stovell, a patient from New York who had cycled through nine different drugs over fifteen years, said. She had lived with constant side effects for more than a decade, until her scans finally showed no sign of cancer.

The treatment isn’t easy. CAR-T therapy can be grueling, with side effects that include fever, low blood pressure, and neurological symptoms. Still, for many, the results speak for themselves. In most patients, the cancer has not returned.

But the promise of a cure comes at a steep cost. CAR-T therapy currently carries a list price of $555,310. For patients already burdened by years of medical bills, that number can be staggering. Yet for those facing the grim reality of advanced myeloma, the possibility of a one-time, life-saving treatment remains a powerful incentive.

For now, CAR-T therapy offers something once unimaginable for multiple myeloma patients: a future.