The most displeasing thing I’ve heard as a writer and student was from a child pointing to one of my poems this week, saying, “You used AI for this.” Now, I didn’t mind that the child in question had a false inclination to believe my writing as artificially generated, but I did secretly mind that he said it with such conviction.

All because of five em dashes.

I’ve always had an affinity for em dashes—Emily Dickinson’s fault, really. I love it when someone recognizes the em dashes in my poetry as a reflection of hers, and I use them everywhere: in poetry, in essays, and even in my Echo articles.

But I digress.

It’s overwhelming how much we’ve come to rely on artificial intelligence for words and how quickly we’ve started distrusting words that aren’t written by it. The line between “human” and “AI” feels thinner every day, and sometimes it seems we can’t even recognize authenticity unless it’s of a lower quality than we expect. We’ve taught the machine to write like us, and now we can’t even differentiate what’s real or not. If you need an em dash to justify whether something is AI-generated, we have a problem.

Over time, we’ve turned writing into a kind of forensic science, hunting for signs of humanity in syntax and punctuation, as if creativity could be measured by imperfection. But here’s the thing: people have used complex words and flourishes long before large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT gained widespread acknowledgment. The Oxford comma predates computers by centuries and so do words like “delve” and “tapestry.” By reducing those stylistic choices into markers of artificiality, we forget that AI does not produce language—it recycles it. It mirrors the corpus of centuries of human expression—from Shakespeare to social media posts—without the heartbeat that gives those words meaning.

And yet, the moment someone writes with precision or depth, we assume it must be synthetic. As if intelligence itself has become suspicious. As if a polished sentence isn’t years of experimentation and thought, but of automation. We’ve created tools meant to extend human expression, but somewhere along the way, we started letting them limit it. Eloquence is increasingly viewed as mimicry and sincerity a matter of suspicion. And that, is the true death of the author.

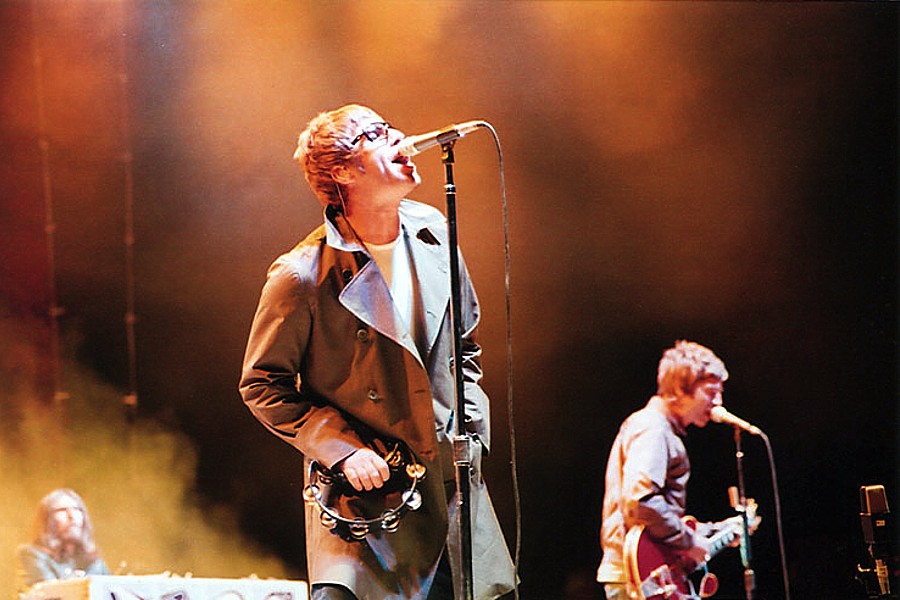

This isn’t the first time a new technology has made us question authenticity. When photography was invented, painters feared it would kill portraiture, according to The New York Times. When typewriters emerged, people claimed handwriting would lose its appeal. Despite concerns, paintings and script are still appreciated, so why all the concern? Here comes the controversy: the thing that sets writing apart from painting and handwriting is that AI has made it so that it’s difficult to differentiate what’s authentic and what’s not. To put things into perspective, it’s like we’re failing to notice that those paintings and script are unique from photography and typed words.

If our best efforts are viewed as artificial, we might start policing diction and punctuation in fear of seeming artificial. We’ll end up flattening our voices to “appear human.” People will begin to lessen their quality of writing to be perceived as human—and that’s the saddest irony of it all. Because the goal of writing was never to sound human. It was to be human: curious, spirited, and alive.

We shouldn’t treat stylistic elements as something to be avoided in fear of being interpreted as AI. And there’s absolutely no need to make educated conversations taboo or reduce it to copying artificial intelligence. Because the answer isn’t to write less well. It’s to write so vividly, so refreshingly, so passionately that no machine could ever replicate the person behind the words and the charm that made language ours to begin with. Writing, at its heart, isn’t a competition with creation. It’s a conversation with it.

So, some of you have been asking me where I stand on AI in writing. I stand with the author.