On “Artichokes”, Seven Years Later

May 6, 2018

In 2011, Yale senior Marina Keegan wrote a widely-read opinion piece in the Yale Daily News called “Even Artichokes Have Doubts”. The article lamented the staggering percentage of Yale undergraduates who choose to undertake careers in consulting despite having found their true passion in another field. Why, she wondered, did aspiring poets, playwrights, and politicians give up the fields that brought them joy for a position at McKinsey or J.P. Morgan? The conclusion she came to was depressing, but perhaps unsurprising: in the end, students valued practicality over passion, and taking a consulting job is perhaps the most practical choice of all.

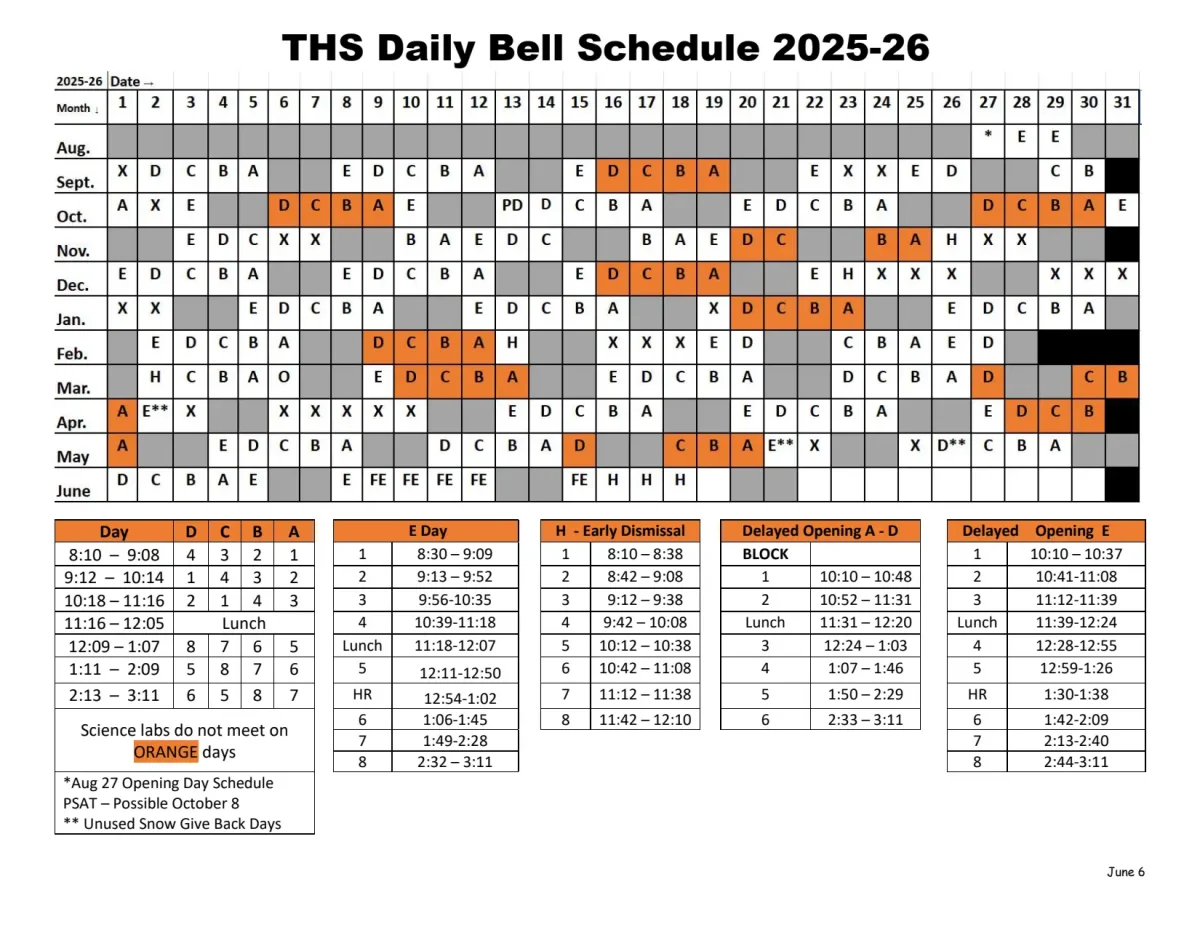

Tenafly High School likely isn’t anywhere close to being the most stressful high school in the United States—that dubious honor goes to one of those infamous high schools in the Bay Area that bear witness to more than five suicides annually—but it’s far from ridiculous to declare it an intensely competitive environment. Tenafly students are infamous for their love of high GPAs and their hatred of anything that implies failure.

I’ve chosen to take AP Chemistry next year, and the first reaction of most upperclassmen upon hearing those two words is usually “don’t do it—it’ll kill your GPA”. Currently, I know of approximately six sophomores who’re planning to take the class next year, and I’ve continuously bemoaned this fact to my friends for the past few months. It was on one of these occasions that a junior turned to me, rolling his eyes.

“Of course everyone’s taking AP Bio instead,” he sighed. “The only thing anyone cares about here is their GPA.”

I’m almost certain he was joking when he said that, but his words got me thinking. AP Chemistry, of course, doesn’t appeal to everyone. There aren’t many high-schoolers who truly love stoichiometry and calculating equilibrium constants. The GPA part, however, rang too true. I’ve seen students go to sleep at four in the morning because of homework assignments—for classes they don’t particularly care about—that are graded for completion. I’ve seen students meticulously calculate and recalculate their GPAs, wondering just how much leeway they can give themselves on a final exam in order to get an A for the course. I’ve seen students put all their faith into numbers, losing sight of what school, supposedly, is supposed to achieve—a cultivation of a lifelong love of learning.

The numbers Keegan lamented were that of yearly salaries, but the numbers we face every day are our GPAs and our test scores. Perhaps it’s hypocritical; I’ve freaked out in the past about not getting the scores I’d hoped for. I’m sure some of my friends are rolling their eyes while reading this very article. Yet these past few weeks, Keegan’s musings on the undeniable value of passion have stayed with me.

Like many other high schoolers, I’ve begun making a list of colleges I want to visit and, perhaps, apply to. My parents, of course, have their own thoughts on this—often, they’ll dismiss a particular college based on its location, the size of its student body, or its strength in particular fields. Sometimes, I’m inclined to agree with them: for example, we share the opinion that I wouldn’t feel comfortable at a school in rural Wyoming simply because of its isolated environment.

In other cases, though, I’ve come to feel almost disenchanted with the process—not simply that of applying to college, but that nameless process in which we, as a society, implicitly equate passions with dreams and dreams with impossibilities. On multiple occasions, I’ve had to justify my interest in schools based on their “practicality”—whether big-time consulting firms like McKinsey recruit there or whether US News and World Report classifies them as target schools for Wall Street firms like Morgan Stanley. I’ve had a deep interest in international affairs for around two or three years now, yet that dream—of working overseas for the State Department, of handling diplomatic relations, of working in international development for the World Bank—is apparently too improbable. Too impractical. Too underpaid, too high-risk, too low in the tangibility of rewards.

I remember when the kid who, in elementary school, wanted to be a businessman was an anomaly; most third-graders expressed hopes of becoming actors, artists, or maybe simply as kind and caring a person as their third-grade teacher. Yet now, I hear “I guess I’ll major in computer science because I heard the entry salary is over 100k” more often than “I want to become a famous musician”.

To our current generation, Mark Zuckerberg is more a figure to base lizard-person/android memes on and less a man to be admired, but there’s one facet of his life story that I do find admirable. It’s undeniable that he loves computer science—loves coding, loves creating programs, loves everything about typing in a series of numbers onto a blue screen to form something almost tangible, something beautiful. I wonder if the thousands of aspiring computer science majors today share this same love.

A few weeks ago, I learned about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Maslow postulated that all humans first had to satisfy their basic needs—those of food, water, and shelter—before attempting to fulfill those ranked higher on his hierarchy, such as affection and appreciation from others. At the top of this pyramid is the need for self-actualization or the realization that you have accomplished the most you possibly could—in other words, the realization that you’ve fulfilled your true passion in life.

I don’t fully subscribe to Maslow’s theory; I find it disingenuous to state that there’s a set hierarchy of our needs when it’s certainly possible for someone to discover their passion and embark on the path to fulfilling it before receiving recognition and respect from others. I would, however, find it deeply disappointing if we never give ourselves the opportunity to explore our passions, to achieve that self-actualization. Perhaps that opportunity seems too distant and dangerous. Perhaps we have faith in numbers—in GPAs, in dollar signs, in the “percentage of graduates who earn over the average entrance salary”—because of their safety. We can interpret them with relative ease—the higher, the better—whereas it’s hard to gauge the fulfillment of a passion.

Despite titling her article after artichokes, Keegan’s more than 4000-word piece never mentions them once. Keegan’s intent, however, is clear: the artichokes, with their frail “hearts”, are us, the confused, hopeful, passionate students with the potential to change the world for the better. Or the potential to become yet another consultant at Goldman Sachs, or another programmer slogging through lines of code, or another teenager slowly giving up on his or her dreams for a lifetime of predictability and practicality.

I’d like to see more high-schoolers take that chance on their passions, though. I’d like to see that aspiring animator enter digital art competitions and seek out internships without the fear of perpetual instability lingering in the back of his or her mind. I’d like to see more students branch out into “weird” majors like Peace and Conflict Studies instead of reluctantly checking the box for finance or pre-med. What I don’t want to see is us, thirty years in the future, becoming the punchline to a midlife crisis joke.