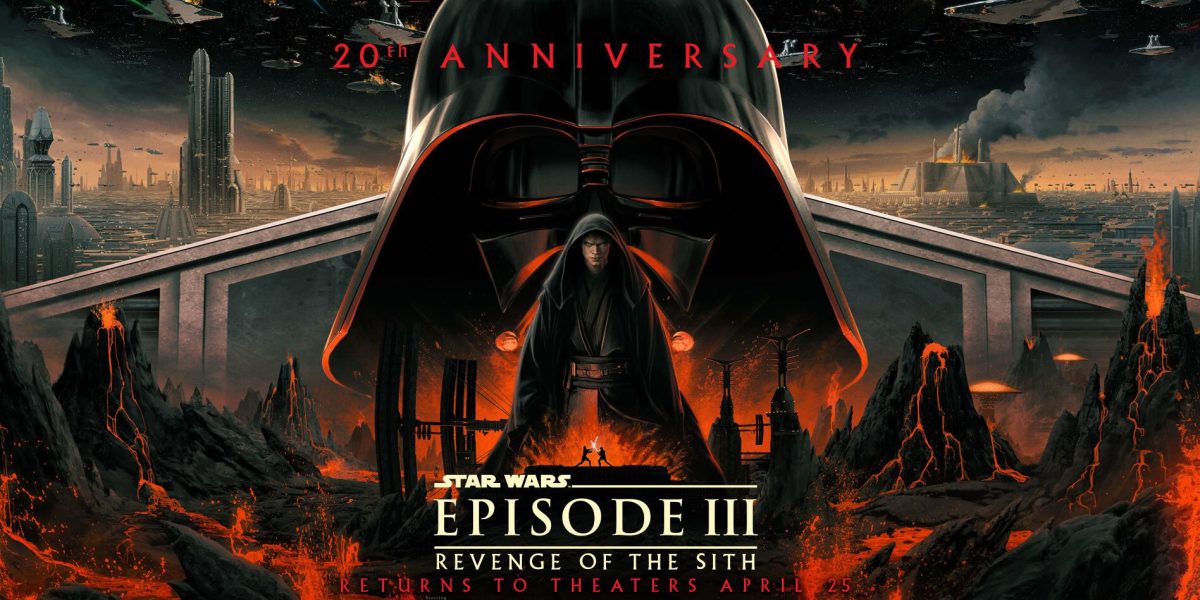

The True Protagonist of Marvel’s “Infinity War”

Marvel’s newest movie might be its most ambitious one yet.

Warning: the following article includes spoilers for Infinity War. If you’re one of the five people who haven’t seen it yet, go do that. If you’re uninterested in nerdy superhero flicks, come back next time for politics (or just read this and try to follow along).

Marvel’s most recent billion-dollar juggernaut, Infinity War, introduced us to the villain to end all villains: Thanos (played by Josh Brolin). A colossus from the planet Titan, Thanos is out to collect the six Infinity Stones (basically just MacGuffins used to give the wielder “immeasurable power”) and, according to him, save the universe. His ideas follow something akin to the Malthusian model, whose creator argued that poverty and famine would be exacerbated in a world with rampant overpopulation. Thanos’s solution to said overpopulation? Annihilate half the universe. Even disregarding his radical (and frankly, wrong) ideas, he’s terrifying—formidable, dominant, and larger-than-life. It only makes sense; with so many heroes to go against, a potent antagonist was all but necessary. But is Thanos the antagonist? One would think so. After all, the Avengers are the good guys. Right?

Well, yes. The Avengers are the good guys. They’re not genocidal maniacs. But a character, contrary to popular belief, doesn’t need to fit somewhere on a moral spectrum to be considered a protagonist. The terms “villain” and “protagonist” (the latter usually being interchangeable with “hero”) are—surprisingly—not mutually exclusive; depending on the framing of the story, a character can serve both roles. In the case of Infinity War, we follow Thanos—in some way or another—obtaining all of the Infinity Stones to wipe out trillions, and the heroes—in some way or another—massively screwing up their chances of keeping him from doing so. That certainly doesn’t sound very heroic. For his calamitous reasoning, though, Thanos is ultimately a sympathetic villain. Terribly flawed philosophy aside, his thinking is grounded in logic: his people shunned him for advocating for an indiscriminate massacre only to die out soon after due to a lack of natural resources. The fact that he’s—somehow—understandable and—somehow—justified in his actions instantly gives him a leg up above other villains in the Marvel Cinematic Universe up to now. His nature as a comprehensible villain is only compounded by the fact that the story functions primarily from his perspective, and that’s what’s so interesting about Infinity War.

A typical three-act structure goes as follows:

Setup: The main characters of the story are introduced.

Confrontation: This is often the longest period of the story; the main characters’ goals become clear, and they resolve themselves to achieving it.

Resolution: As “the final showdown,” the resolution is routinely the shortest—at this point, the protagonist is usually face-to-face with the antagonist(s) already, and they’re about to fight. After that fight comes the denouement, where loose plot threads are tied up and the story concludes.

Most films you know likely follow this formula, and that’s because it works. In the context of a standalone movie, it fills in all the gaps—it introduces you to the protagonist and his/her motivations (setup), it shows the protagonist overcoming obstacles in his/her way (confrontation), and concludes with the protagonist accomplishing his/her goal (resolution/denouement). That’s what confused me so much about Infinity War. I mean, it’s an Avengers movie. It says so, right on the title. But which Avenger is it actually about? Through whose eyes do we experience this three-act structure? Then it occured to me: it’s not an Avenger’s. It’s Thanos’s. Thanos, the “villain to end all villains,” might actually be the hero of Infinity War. Let me explain.

The beginning of the movie takes place right after Thor: Ragnarok, where Thanos and his guild, the Black Order, has destroyed an Asgardian ship on the hunt for the Infinity Stones. That’s his motivation, and in watching him take the Space Stone we see him answer the call to adventure. He sends the Black Order to Earth to collect the two Stones there and rendezvous with him on Titan. Setup.

Thanos moves on to Knowhere, and he gets the Reality Stone from the Collector. On the way, he beats the Guardians of the Galaxy. Ignoring any preconceived notions of heroes and villains, the Guardians are simply obstacles for Thanos to overcome. After inevitably defeating them (as heroes do), he takes his daughter—Gamora—to Vormir and sacrifices her for the Soul Stone. This hits hard, and reinforces his drive to finish the mission. He heads for Titan, but the antagonists of the story have fooled him—one of his allies are dead by their hands, and they still wield the Time Stone. Meanwhile, others who oppose him intend to destroy the Mind Stone on Earth. All seems lost. Confrontation.

Having beaten his enemies on Titan (and subsequently taken the Time Stone) Thanos departs for Earth. He reaches the Wakandan battlefield, where three more of his Black Order have been terminated, and attempts to take the Mind Stone from the Vision. However, his opponents succeed. The Mind Stone is gone, and Thanos has been defeated. However, Thanos uses the Time Stone—something he’s found on his journey—and is able to collect the final Infinity Stone to complete his Gauntlet. Despite Thor’s last-ditch effort to stop him, it’s too late. Thanos snaps his fingers, and half of the known universe ceases to exist. The hero has won. Resolution.

Within the Soul Stone, Thanos sees a vision of Gamora. She asks him what it cost. He simply responds with “Everything.” Though he’s collected all six Infinity Stones and finished his quest, he has to accept what he’s lost—namely, the only thing he’d ever loved. On a distant planet, far away from the chaos on Earth, he watches the sunrise. Denouement.

Now, it’s doubtful that Infinity War will have many lasting consequences for the Marvel movies moving forward. That much is almost assured, considering that they killed off characters already signed on for sequels in the near future almost guaranteed to do incredibly well at the box office. (Black Panther, I’m looking at you.) However, I firmly believe there’s something more to the movie than just in-universe consequences. True, the Avengers are the bonafide “good guys” of the movie, but Thanos is the leading character—no, the hero. What does this mean for the movie? A lot. Making Thanos the main character changes the ballgame entirely: the question shifts from “can they beat Thanos?” to “can they survive Thanos?” And the answer, definitively, is no. That’s where the narrative genius lies; after spending ten years refining the stereotype of “the heroes always win,” Marvel turned the entire concept on its head.

A big problem people often point to when analyzing the Marvel Cinematic Universe is, well, the fact that it is a cinematic universe. It makes it difficult for each film to feel strong independently, as if it needs to be connected to all of the others in some way for the audience to get the full impact. Though this is, in some ways, the case for Infinity War, I firmly believe that—with even a basic comprehension of the previous films (Civil War in particular)—the plot is easier to grasp than most of the other movies in Marvel’s lineup; this is in no small part due to the use of Thanos as the protagonist. Infinity War is easily one of the strongest in a long list of predecessors (eighteen, to be exact), and I’m sure that its unorthodox narrative choices will be talked about even years after the movie has gone out of theatres.

Aiden Kwen ('20), Senior Editor, is interested in interactions between pop culture and social issues; as the president of the Controversy Club at THS and...