Yes, There Was a Blue Wave

November 15, 2018

As it neared midnight on November 6, the headlines concerning the results of the 2018 midterm elections were surprisingly bleak. Many media outlets seemed to imply that, with the presumed defeats of Andrew Gillum in Florida and Beto O’Rourke in Texas, the Democratic “blue wave,” which had been lauded for almost a year, had failed to manifest. Indeed, merely two days after the election, New York Times Opinion Columnist Bret Stephens published an editorial titled “The Midterm Results Are a Warning to the Democrats,” in which he described the results of the elections as “In a word: meh.”

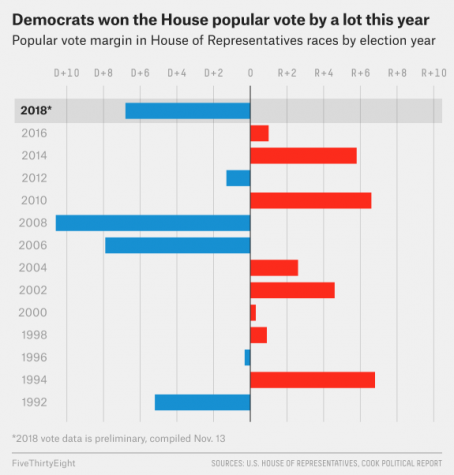

Yet as the results trickled in, slowly but surely, it became clear that there had, indeed, been a Democratic wave. As of November 11th, the polling and statistical analysis site FiveThirtyEight predicts that Democrats will gain 38 seats in the House of Representatives. Democrats also picked up seven governorships, gained control of the governorship and both state legislatures—a trifecta—in seven states, flipped two Senate seats, and picked up more than 300 state-level legislative seats.

Although Republicans are poised, at the moment, to end this election cycle with two additional seats in the Senate, it seems prudent to remind ourselves that the Senate map Democrats were faced with this year was one of the most difficult in decades. Even in 2016, it was acknowledged by Politico that “Democrats may take back seats in the House, [but] winning back the Senate is almost impossible, given that they will be on offense in just two battlegrounds, Arizona and Nevada, and defending 25 seats.” Back in 2016, however, it also seemed within reach for Republicans to pick up enough seats in the Senate to form a supermajority. In that context, the results in the Senate for Democrats aren’t simply “meh,” as Bret Stephens would label them: they’re positively relieving.

Perhaps more important than affirming that a blue wave did occur, however, is analyzing the factors which helped it come to be. The most important underlying factors are remarkably simple: grassroots organizing, running candidates—good ones—everywhere, and creating coherent messages which appeal to voters. The big story of this particular midterm election has been turnout: more than 49% of eligible voters cast ballots, the most in a midterm election in more than a hundred years. Yet such a high turnout wouldn’t have been possible without the aforementioned underlying factors.

Grassroots organizing may sound like yet another political buzzword, but if it is, it’s a remarkably effective one. Decentralized volunteering, much of which was coordinated by outside, non-establishment groups like Swing Left operating independently of one particular campaign, was critical to the Democrats’ success in many House races. According to The New Republic, “the number of volunteers mobilized over the last 18 months exceeded two million people.” Volunteers were also dispatched to areas which differed dramatically from normal canvassing turf: they went “to places [where] traditional Democratic consultants never bothered to go.”

Running strong candidates in as many districts and states as possible seems like a remarkably simple idea, yet it’s one which often doesn’t come into practice. Former Democratic National Committee (DNC) Chair Howard Dean’s 50-state strategy, which aimed to build fertile ground for the Democratic Party in every state, was controversial, yet while the strategy was in place, “In the 20 states [analysts at Governing] looked at—those that have voted solidly Republican in recent presidential races—Democratic candidates chalked up modest successes, despite the difficult political terrain.” This year, Democrats took heed of that lesson: according to Reuters, the DNC made “six-figure investments in 85 districts, including many once seen as safely Republican,” in anticipation for the 2018 elections. By doing so, Democrats brought about a blue wave, one which managed to even flip Oklahoma’s 5th Congressional District, regarded as solidly-red up until the results rolled in.

Of course, messaging was critical as well. Exit polls demonstrated that healthcare was by far the most important issue for 41% of voters, and even as Democrats around the nation campaigned with different proposals on how to best resolve America’s healthcare crisis—from a single-payer solution to simply preserving the Affordable Care Act—there was one central message which Democrats conveyed: we will expand Medicaid, preserve protections for those with pre-existing conditions, and work to truly make healthcare more affordable. Yet messaging on local issues, too, was important. Beyond the big-ticket issues of healthcare and gun control, Tom Malinowski campaigned on the construction of the long-awaited Gateway Tunnel, Antonio Delgado campaigned on increased protections for upstate New York’s small farmers, and Abigail Spanberger campaigned on preserving the parks and wildlife of Virginia.

This blue wave was not simply a culmination of anti-Trump sentiment. Nor was it inevitable, or the product of voters wishing for a “breath of fresh air.” It was the result of organization: organization of volunteers, candidates, and messages. That, however, only makes it all the more replicable.