Márquez and Magical Realism: Why You Need to Read One Hundred Years of Solitude

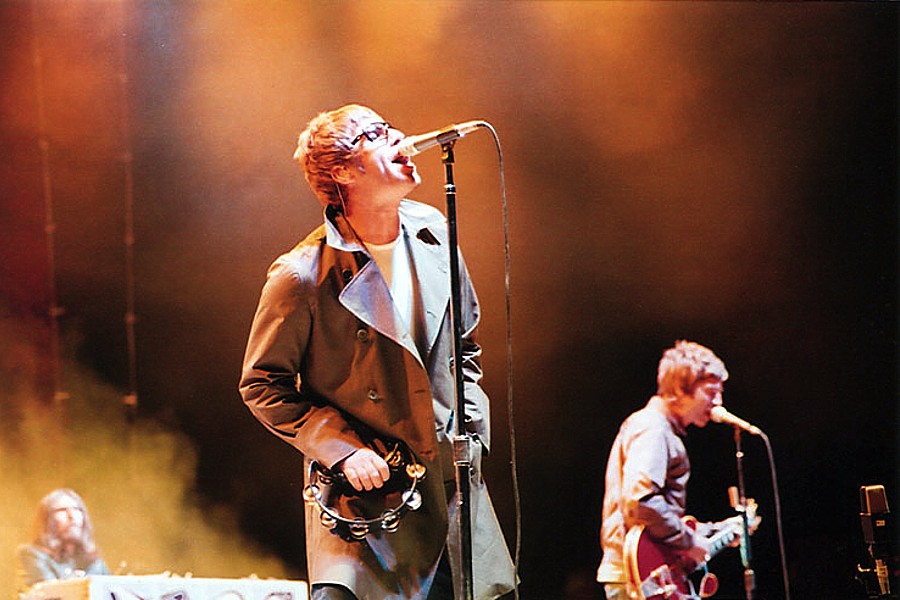

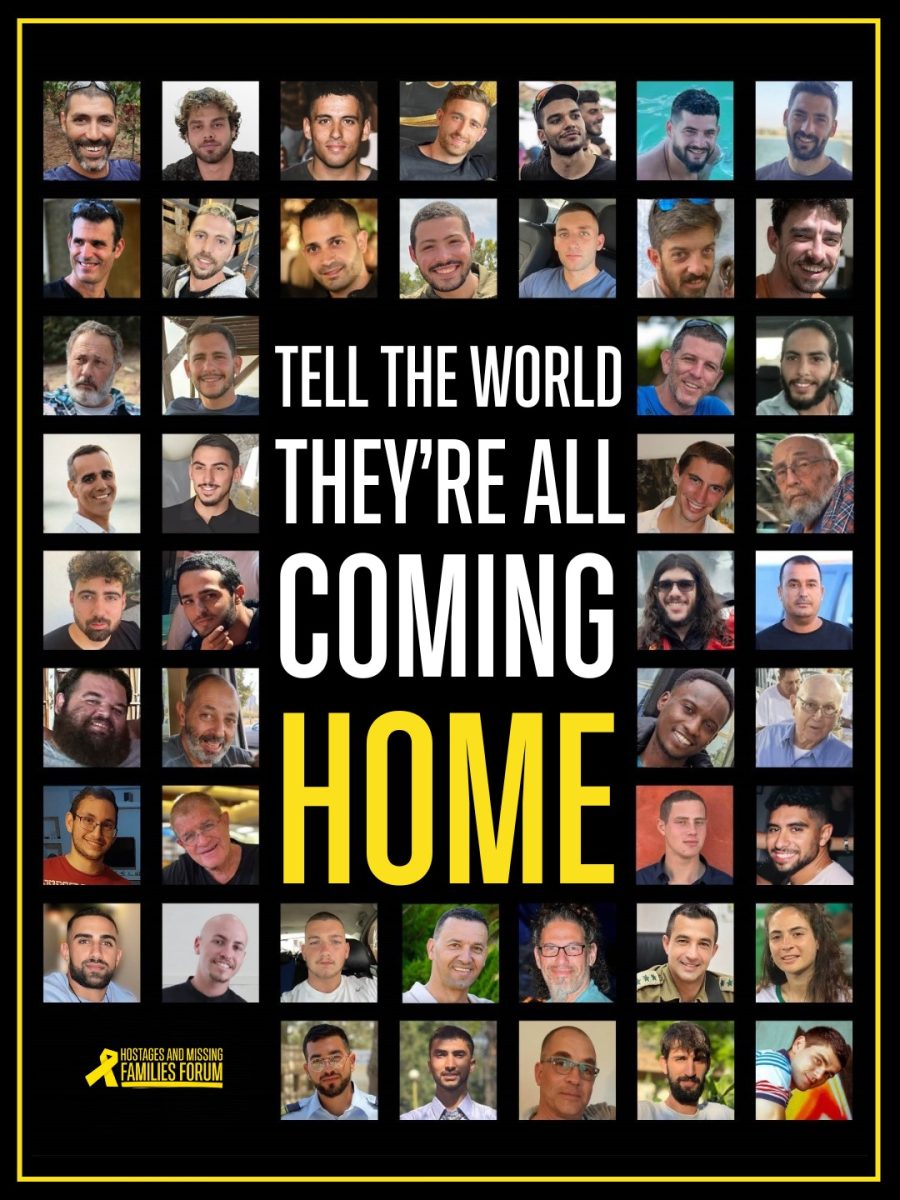

Soledad Amarilla / Ministerio de Cultura de la Nación

Painting depicting Gabriel García Márquez and his work that reads “The magic year of García Márquez”

June 2, 2020

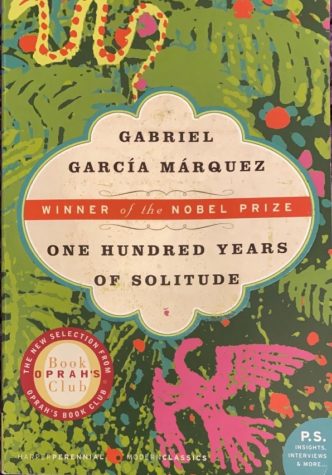

The New York Times regards the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez as “the first piece of literature since the Book of Genesis that should be required reading for the entire human race.” Pablo Neruda, the famous Chilean poet, said that it is “the greatest revelation in the Spanish language since the Don Quixote of Cervantes.” The book not only popularized magical realism as a genre, but also Latin American literature as a whole. It allowed the forgotten stories of the people from a continent deeply affected by colonization to be told.

Márquez was born Gabriel José de la Concordia García Márquez on March 6, 1927, in Aracataca, Colombia. He received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982 “for his novels and short stories, in which the fantastic and the realistic are combined in a richly composed world of imagination, reflecting a continent’s life and conflicts.” This novel allowed Europeans to gain a new perspective on the reality of colonized nations. Despite leaving Colombia for Mexico, and dying there (in 2014), upon his death, Juan Manuel Santos, the former president of Colombia regarded Márquez as “the greatest Colombian to ever live.”

One Hundred Years of Solitude was written during the Latin American Boom of the ’60s and ’70s and helped spread the genre of magical realism throughout other nations to tell stories of identity and of the colonized and/or oppressed. Not only is Márquez the most well-known writer in this movement, One Hundred Years of Solitude, which was published in 1967, is the most well-known work. This book has sold over 50 million copies and has been translated into 46 languages. In fact, Márquez regarded the English translation of his novel by Gregory Rabassa to be superior to the original. The entire story can almost be seen as a retelling of the Bible as the world in which the characters live becomes adulterated and confusing as time passes. He based the fictional setting of his novel, Macondo, on his birthplace of Aracataca, though the location of the novel is never explicitly mentioned in the text. It follows José Arcadio Buendía and his wife, Úrsula Iguarán, as they found the town of Macondo as well as the following five generations who live there. Throughout the novel, several Buendía’s try to decipher the manuscripts written in code in foreign languages that were written by a gypsy, Melquíades, who was a frequenter of the village. Melquíades claims on page 184 that “No one must know their meaning until he has reached one hundred years of age.” It takes place between the mid-1800s, to the mid-1900s. During these years, Latin America, and more specifically Colombia, went through massive changes that altered the nation forever, and which are captured in this novel.

Márquez’s book falls under the category of magical realism. The term magical realism was coined by Franz Roh, a German art critic who used it to describe the painting style, New Objectivity, that was gaining popularity in Germany. He described his term magical realism as art that portrays “the ‘magical’ nature of the rational world.” It is a genre in which “the supernatural is presented as mundane, and the mundane as supernatural or extraordinary.” There is a lot of debate on what exactly magical realism means, but magical realism is essentially any form of art that takes a realistic story and sprinkles it with elements of magic while still applying the laws of the real world. While works in this genre do not seem realistic, they do not seem entirely fantastical either. This is not to be confused with surrealism, as magical realism intends to discuss everyday life on earth while incorporating magical elements, while surrealism does not attempt to be realistic and instead attempts to bring the reader into a completely alternate reality. Films that incorporate elements of magical realism include Midnight in Paris, Amélie, and The Green Mile. While there is some disagreement as to the origins of the genre given that European artists such as Franz Kafka and Nikolai Gogol have published stories that would certainly fit into that category, the genre is typically associated with Latin American Literature.

Magical realism rose to popularity in South America during the 1940s. This is because a lot of magical realism deals with contrasting themes of pre- and post-colonialism. Many works compare and contrast the ideas of traditional life versus modernization, urban versus rural, European culture versus that of Native Americans. By blending these ideas together, a world is created that is neither one nor the other, neither entirely realistic nor entirely fictitious. In magical realism, the magic is never fully explained as doing so would make it seem unrealistic. The magical elements are made out to seem normal. Many influential Latin American Magical Realism authors include Jorge Luis Borges, Alejo Carpentier, Miguel Ángel Asturias, and Isabel Allende, while non-Latin American ones include Toni Morrison, Louise Erdrich, and Yaa Gyasi. These authors blend reality with magic while discussing oppression.

A popular theme within many works of magical realism is that of incorporating cyclical time as opposed to linear. Events and ideas tend to reappear and repeat themselves throughout the entirety of the story. The same errors occur year after year. They also include many motifs, such as The Black Tyger from Okri’s The Famished Road. Magical realism stories are typically about people who are underdogs or who hold little power. Works in this genre can be used to make political statements about class, gender, or government. Carnivals also often tend to be portrayed, and they are portrayed differently depending on what part of the world the writer is drawing inspiration from. South American authors illustrate the entertaining and amusing aspects of a carnival, however, behind all the fun many Latin works depict political conflicts and struggles that reflect the times.

Alejo Carpentier, a Cuban writer, discussed that magical realism is inherently Latino as “indigenous communities there often did not draw as fixed of a line between the natural and the supernatural as their European counterparts.” Gabriel García Márquez, agrees. Indigenous South Americans have always had a surrealist outlook. Works like his give a voice and individual identity to a Latin America that is not influenced by colonizers.

One Hundred Years of Solitude integrates childlike elements of fantasy and romance along with its battle scenes as Márquez stated that his early years were his best years. He explores ideas of the significance and insignificance of human thought. For one, a good portion of the novel is dedicated to describing Colonel Aureliano Buendía’s meaningless process of creating little goldfish “pescaditos de oros” in solitude. Particularly in this line on page 132, we see these fantastical elements play a part in the story in a meaningless way as the blood on a man moves through the village: “a trickle of blood came out under the door, crossed the living room, went out into the street, continued on in a straight line….went in under the closed door….hugging the walls so as to not stain the rugs.” Other instances of magical realism include flowers falling from the sky, a room remaining clean in spite of years of neglect, rain lasting for years, and the miraculous survival of a bullet that went through a man’s body.

Now, Márquez’s novel is not an easy read. In its 417 pages, Macondo changes from a simple village in which no one has ever died into a bloody war-torn battle zone that sees the rise and fall of the Buendía family. It is filled with civil wars, nostalgia, plagues, incest, love, loss, repetition, and of course, solitude. The concept of time also seems very distorted. Months and years change drastically from chapter to chapter, page to page, and even within the same sentence. The very first line of the book is one example of this: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” All male members of the Buendía family tend to be named either some form of José, Aureliano, or Arcadio, while the girls are named Úrsula, Remedios, or Amaranta. The repetition of names is a nod to the idea that the Buendías will go through the same hardships generation after generation and will repeat the mistakes of their ancestors. On page 181, Márquez writes, “While the Aurelianos were withdrawn, but with lucid minds, the José Arcadios were impulsive and enterprising, but they were marked with a tragic sign.” This is also shown on page 335 with the line, “…time was not passing…it was turning in a circle.” The repetition doesn’t only end there; the events that go on in the entirety of Colombia seem to happen more than once as if the whole country were in a loop of victories, wars, visitations of gypsies, and solitude.

Macondo begins as a paradise-like town isolated from the rest of the country. As it slowly gains connections to the outside world, turmoil ensues that ultimately leads to the downfall of Macondo. Although the town is isolated at the beginning of the novel, the inhabitants of the village remain in solitude throughout. We see the effects of different kinds of solitude, for better or for worse. It is up to the reader to decide whether solitude is a necessary part of life. Another motif is the questioning of the existence of God and his varied presence in the lives of the Buendías. In spite of the fact that they live with many people, they separate themselves from humanity for a plethora of reasons typically having to do with the pursuit of knowledge. Vulgar language is only used for the first time once the turmoil has begun to symbolize the end of the innocence of the village.

Although it is a fictional story, certain events that occurred in Colombia and the surrounding areas between the 1800s and 1900s play a role in the story. Among these events include The Thousand Days’ War, a Colombian civil war in which the Liberal party fought against the Conservative one, which ended with the Treaty of Neerlandia. The book recounts events that occurred in Riohacha, Colombia including those related to The Thousand Days’ War and Francis Drake, an English pirate. The novel also discusses the arrival of the Europeans and the effect they had on the nation. Most notably, however, the book describes the Banana Massacre of 1928 that occurred due to European neo-colonialism. How neo-colonialism worked was that Europeans brought new inventions and industries to South America and set up job opportunities for the natives who lived there on their own land. Many of the jobs were related to banana cultivation. American writer O. Henry offensively called nations whose income relied entirely on one product, such as bananas, Banana Republics, though many of these countries that used to be called this would no longer fit under that definition. Eventually, these banana companies would form the United Fruit Company, which would later become Chiquita. However, these workers worked under horrible conditions. They were not under contracts, nor paid well, and their labor was abused. The workers then decided to go on strike. When they did, the Colombian army shot and killed between 47 and 2,000 men, women, and children. In One Hundred Years of Solitude, we see the story told through the perspective of the workers present, as well as the gringos who try to convince the population that this event never occurred and they succeed in doing so. Even in the novel, the characters do not believe the two witnesses of the event who keep repeating what happened as they recall them. This is a nod to the fact that Latin history from the perspective of those being colonized is often neglected and forgotten.

In spite of Márquez’s staunch stance that One Hundred Years of Solitude not be adapted into a movie, Márquez’s sons, Rodrigo and Gonzalo, have sold the rights. They will be executive producers on the series that is set to appear on Netflix in 2020. Márquez also requested that if his novel was to be adapted, it would be in the language of its original publication, Spanish, and be called Cien Años de Soledad. Márquez’s son’s names make an appearance in this novel. Gabriel García Márquez is even the name of a minor character.

This book is the quintessential Latin American novel that depicts the reality of Latinos experiencing and trying to comprehend their rapidly changing reality. Copies are available on Amazon, as well as Barnes and Noble.