A Jewish Christmas

Christmas Tree Snow drawing (Vector cliparts) christmas,snow,tree,winter,decoration,outdoor,garland

January 5, 2022

At six years old, my birthday wish was likely different from that of most children. I was never determined to fly into space, nor did I ever dream of receiving a million dollars to spend on new toys. Instead, on my birthday, I closed my eyes, ready to blow out my candles, and thought, ‘I wish I could celebrate Christmas.’ Delighted by the strings of colorful lights wrapped around the siding of my neighbors’ homes, I watched with envy as grandmas and grandpas trickled into the doors of other kids—kids who had likely been anticipating this morning for weeks. Feeling almost betrayed by the scent of warm jelly donuts and potato pancakes, I spent most of those Yuletide mornings staring outside our large, living room window with a tempered glare.

Despite my deep sentiments, however, I was ashamed of my envy. I would remain silent when my school friends compared their birthday wishes with one another, feeling embarrassed when they’d later ask to hear mine. I’m not sure what prompted me to lie; maybe it was my mother’s disapproval or the Star of David hanging around my neck that felt like a badge of guilt. Either way, I could not muster the words that I believed would produce a scandal more widespread than Nixon’s Watergate debacle. Instead, I’d proudly remark, at the risk of sounding like every other first grader, with the classic response, “More wishes!” They, of course, having heard this response thousands of times, would sigh and walk away. I, filled with contentment at my lie’s success, used this response routinely, and that idea worked… for the most part.

My mother, who, in addition to never having failed at detecting my dishonesty, had always been proud of our Jewish heritage. In fact, on the night before every Jewish holiday, she’d gather me and my brother around the kitchen table and quiz us on the various origins of every holiday tradition. For instance, on the night before Rosh Hashana, each sibling would offer a reason for eating pomegranate seeds, a tradition that symbolizes sanctity, fertility, and abundance in the Jewish New Year. My mother incentivized us by explaining that we’d be the most “knowledgeable kids” at the dinner table, while my brother and I, uninterested by the title, would nod perfunctorily. That Hannukah, when my brother and I sat down around the kitchen table in preparation for my mother’s questions, I found myself revealing my deep secret with a question.

“Mom, why don’t Jews celebrate Christmas?”

She, in a pit of curiosity, asked for the reason behind my unexpected question. At that moment, I understood that my secret was revealed and that lying, although enticing to my young mind, would only provoke more questions by my curious mother. As my chin fell to my chest and my eyes drooped, I mumbled in a low voice, “Christmas just looks pretty cool.” My mother laughed nonchalantly, explaining that she, too, felt that Hanukkah could become more festive. Her response (although surprising me to this day) filled me with a great deal of relief at the time.

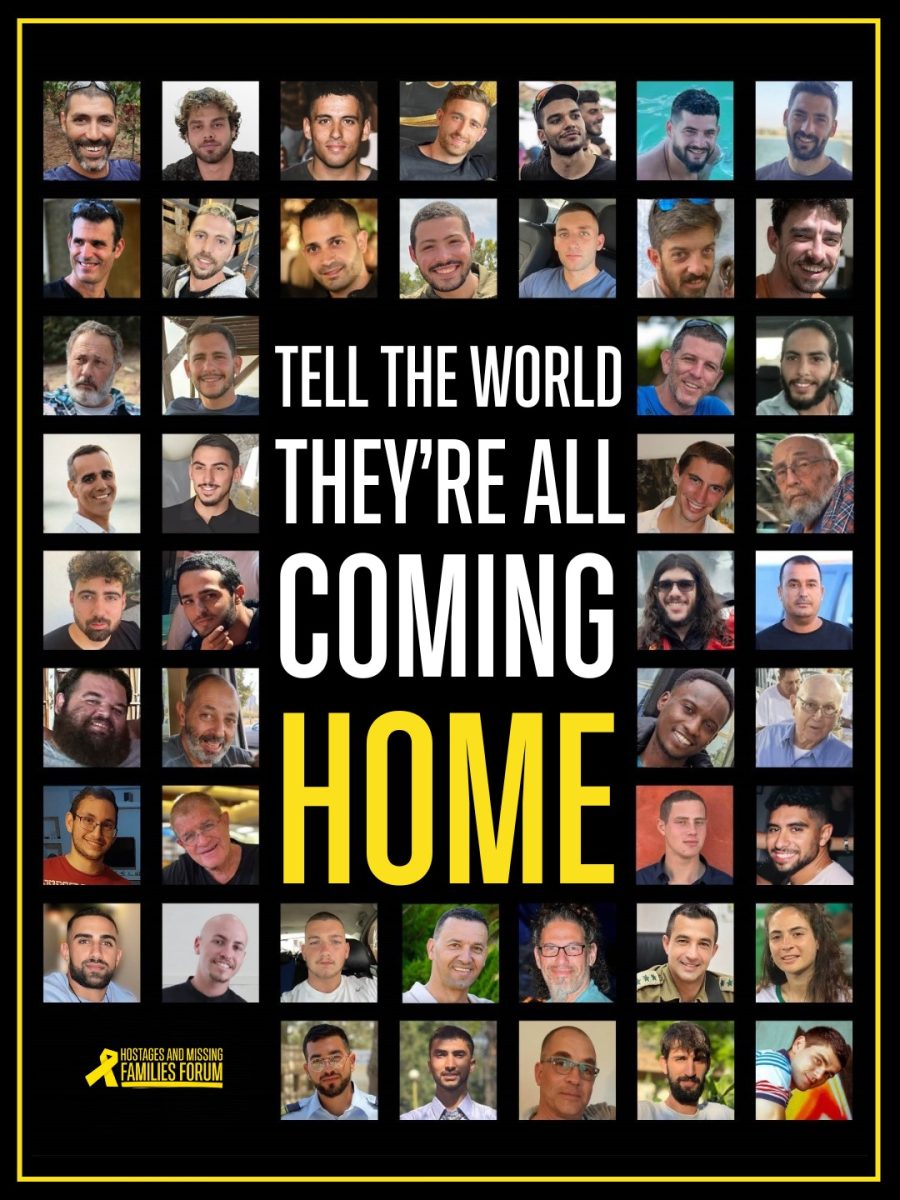

Since that night, my mother and I have cherished the tradition of decorating our house for the eight nights of Hanukkah. Every year, we paste clusters of small menorah stickers on our windows and string a mix of blue and silver lights around the siding of our house. Although I do not celebrate the special holiday of Santa and reindeer, I’d like to tell my young, six-year-old self that I celebrate something not far from that holiday: a Jewish Christmas.