From trying to decipher handwriting from the Revolutionary War to struggling to read a grandmother’s letter, the elegant writing of cursive is currently serving as a barrier to children around this country. The sophisticated loops and curves of the pen often scare children. For this reason, across the U.S. during the year 2010, schools began to support the “anti-cursive trend.” Soon after, several states set aside cursive in exchange for Common Core standards, a curriculum in which cursive is absent. Due to this dramatic change, recent children’s capability to read or write any other form of penmanship in lieu of print has diminished.

As a solution to these problems, states are becoming more inclined towards the instruction of cursive writing. As of January 1, 2024, California’s law mandated students to start utilizing cursive in school, adding onto the prior 23 states that have already readopted cursive in their curriculum. With the addition of California, 24 states are requiring cursive into the curriculum, raising the number of states to be about half of the total states in America. As for New Jersey, cursive isn’t required in schools, but over the years, such legislation regarding cursive education has been brought up twice. About half of the U.S. is now implementing cursive into their elementary school curriculum, and the other half may quickly follow suit.

There are still ongoing arguments about mandating the instruction of cursive amongst educators. Some say that cursive isn’t useful in daily life, and during the time spent learning cursive, some state that students are better off further enhancing their typing skills on the keyboard or working on their academics. “It should be an enrichment not a requirement. It will never be needed in life, except for a signature, and those will be electronic before long,” Michelle P. Williamson said in a debate on the National Education Association website.

Others claim that cursive trains the brain to learn motor skills and memorization, indicating that students will have better handwriting by learning cursive. In addition to the benefits, educators who are for cursive instruction also emphasize the day-to-day advantages of cursive. “You can’t open a bank account without a signature,” said Joseph Adams, a state representative for Pennsylvania, one of the five states currently considering the legislation for cursive writing. “You can’t open a credit card without a signature. You can’t buy property without putting a signature together on a contract, an agreement, or a deed. All of those things are important.”

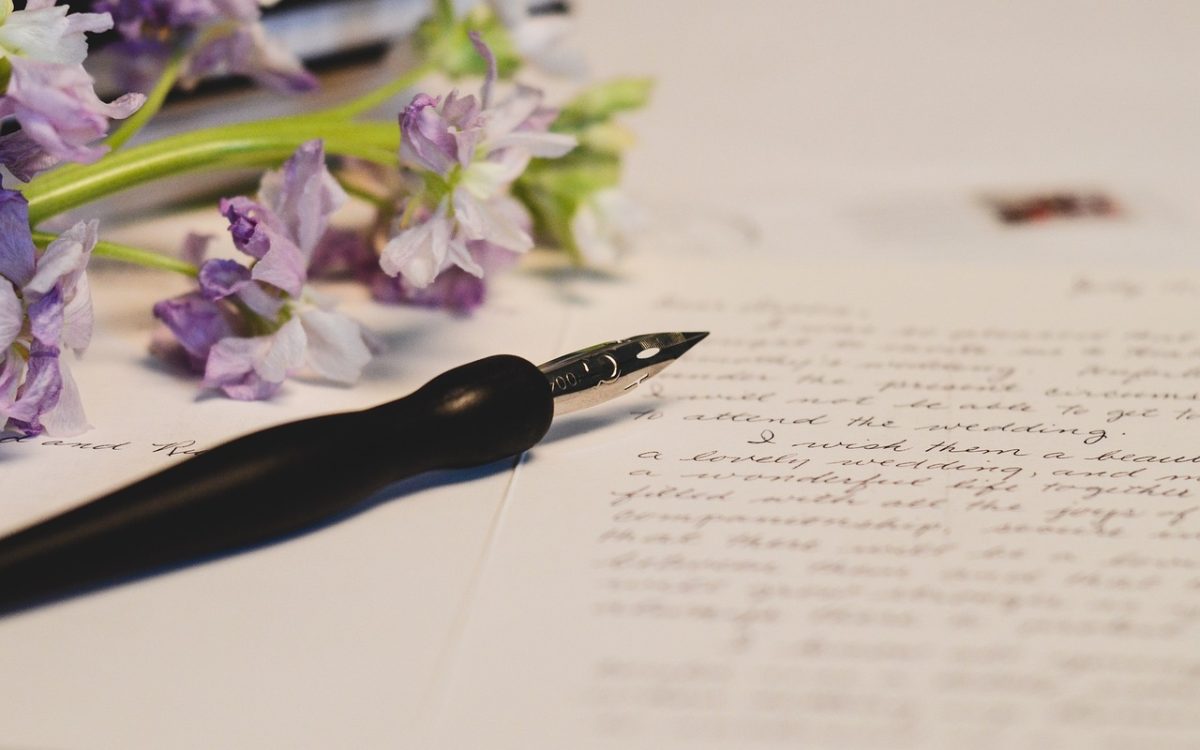

With recent developments in technology, it’s easy for people to forget the old form of handwriting they learned in elementary school. Instead of practicing handwriting, students prefer playing with the fonts in their electronic devices, neglecting the beauty of pen on paper. For this reason, cursive has become a form of lost art. In addition to this lost form of writing, parts of history are also ebbing away from revealing their unique stories. The National Archives has released a “Revolutionary War Pension Files Transcript Mission,” a project in which they are gathering volunteers to decipher 80,000 soldiers’ letters from the Revolutionary War from 250 years ago. What’s interesting about these letters is that they are all cursive that needs transcribing. The lack of cursive readers has influenced our perspective of history entirely, needing to go as far as to “decipher” the letters of the words once widely known.

The artistic and personal benefits of cursive have allowed people to reconcile with the art and make the argument for cursive to return to the school curriculum. Cursive proves to be both the refined penmanship that puts everyone who sees it in awe and a highly beneficial form of education for it also contributes to our understanding of history. The recent reintroduction of cursive writing sheds the possibility of hope that the lost art of cursive could return.