Liparidae, more commonly known as snailfish, are deep-ocean dwellers that resemble tadpoles. These creatures, with their oversized heads and gelatinous bodies, are well adapted to life in extreme pressures and the darkness of the deep sea. Now, scientists have discovered a total of three new species within the family hiding far within the Pacific Ocean.

Researchers from the State University of New York at Geneseo, the University of Montana, and the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa reported the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute’s (MBARI) findings, describing the three species of snailfish in Ichthyology and Herpetology.

According to MBARI, two of the three new species—the Careprotus Yanceyi, or dark snailfish, and Paraliparis em, or sleek snailfish—were discovered at Station M, which is located 130 miles off the central coast of California. A team of researchers led by MBARI’s senior scientist Steven Haddock used Alvin, a deep-diving submersible, to explore depths of over 4,000 meters, where they discovered both species. This site, which is operated by MBARI, has been a key site of exploration for more than 30 years.

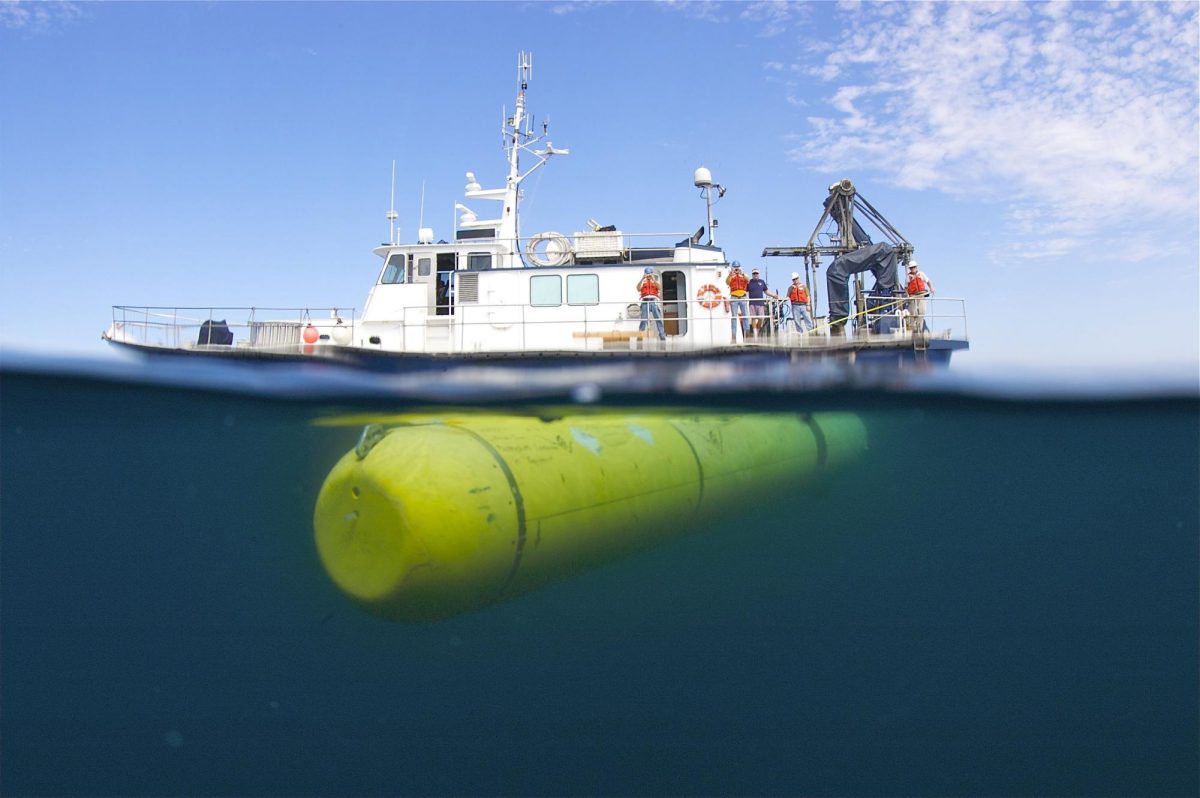

The third species, Careprotus Colliculi, or bumpy snailfish, was discovered in Monterey Canyon, around 100 kilometers offshore. Found at the depth of 3,268 meters, it was observed and collected during an expedition aboard MBARI’s retired flagship vessel Western Flyer, using the remotely operated vehicle Doc Ricketts.

Unlike other species in the liparidae family, these newly-discovered snailfish have their own distinct appearances and adaptations. The bumpy snailfish is a small, bubblegum-pink fish that measures around 9.2 centimeters. It has a round head with large eyes, wide pectoral fins, and a bumpy texture on its body. It is “pretty adorable,” Dr. Mackenzie Gerringer in Smithsonian Magazine said.

The dark snailfish has a black body with a round head, contrasting with its bumpy cousin, and features a horizontal mouth. It was named after the deep-sea biologist Paul Yancey, whose work has been instrumental in understanding how animals adapt to high-pressure environments.

The sleek snailfish is the most commonly found of the three. It has a long, laterally compressed body with an angled jaw and lacks a suction disk on its body. Its scientific name pays tribute to Station M and the decades of research conducted there.

Although MBARI and other institutions have studied areas like Station M, discoveries highlight just how much remains unknown in the deep ocean. “The fact that undescribed species of snailfishes were collected from the same place, on the same dive, at one of the better studied parts of the deep sea in the world highlights how much we still have to learn about our planet,” Gerringer said in an interview with IFL Science.

Steven Haddock emphasized the importance of sharing data and tools with the scientific community, noting that such collaborations often lead to new discoveries.

“MBARI seeks to make ocean exploration more accessible by sharing our data and technology with our peers in the science community,” he said on the MBARI web site. With each new species, scientists gain another puzzle piece in understanding our Earth, and as ocean ecosystems face increasing threats from climate change and human affairs, documenting and exploring the deep-sea biodiversity has never been more important.