For decades, the ozone layer has been one of the most visible symbols of human degradation on the planet. First identified in the 1980s, this thinning ozone layer over Antarctica sparked urgent concern as scientists warned of its link to rising skin cancer rates, ecosystem disruptions, and climate shifts. The crisis became a turning point in realizing the dangers that the growing hole is causing. Today, thanks to global efforts, scientists report that the ozone layer is on track to recover within this century, encouraging people to adopt more environmentally friendly practices to prevent its depletion.

So, what is the ozone layer? The ozone layer is a thin region within the stratosphere, the second layer of Earth’s atmosphere. Ozone, made up of three oxygen atoms, is constantly formed and broken down in a natural cycle. This layer plays a critical role by absorbing more of the sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation, shielding humans from skin cancer, cataracts, and other diseases, while also protecting crops, materials, and the marine ecosystem. National Geographic compares the Ozone layer “like a sponge,” explaining how it “absorbs bits of radiation hitting Earth from the sun… [and] acts as a shield for life on Earth.”

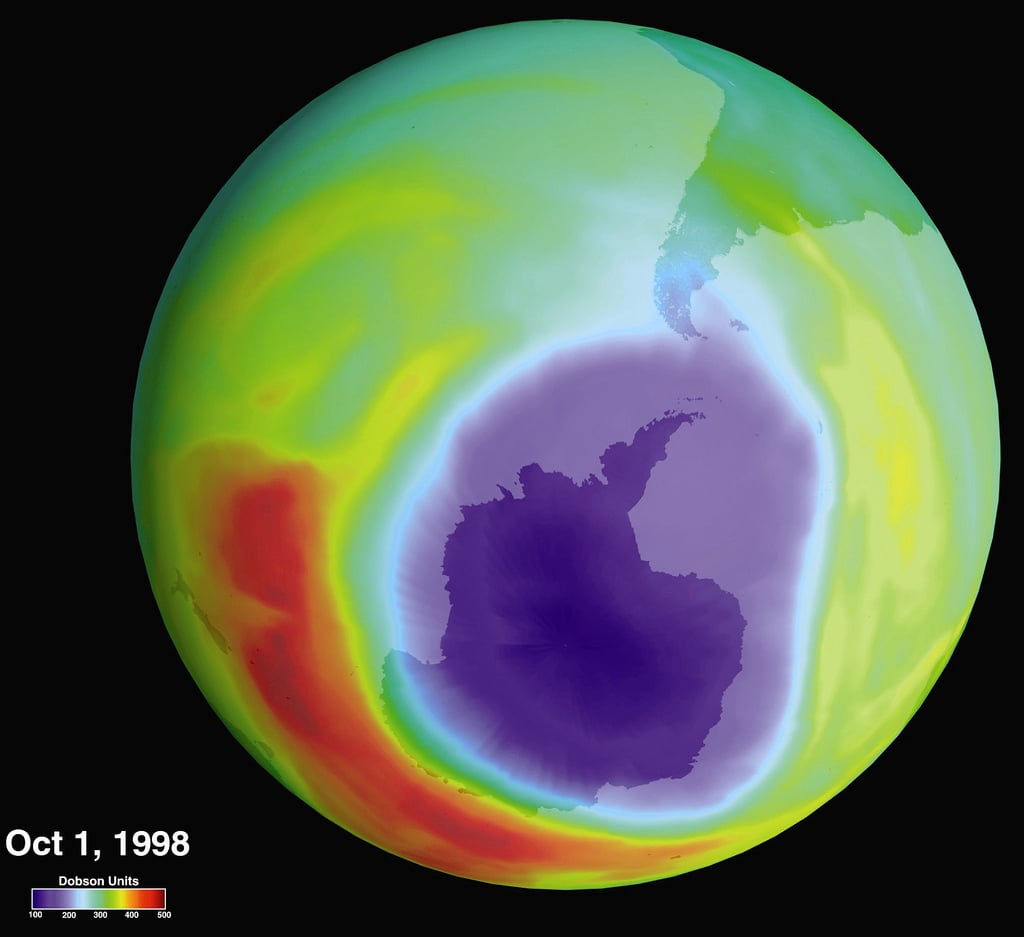

Because of its vital protective role, the discovery of the ozone hole raised urgent concerns regarding the health of humans and, more importantly, Earth. According to NASA, the ozone hole is “a human-caused hole,” due to the use of gases like chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in spray cans which, “break down ozone molecules in the upper atmosphere.” While often confused with global warming, the ozone hole is a distinct issue: ozone depletion results from chemical reactions in the stratosphere, whereas global warming is primarily driven by greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane, which trap trapping heat in the lower atmosphere, according to NASA Earth Observatory. Still, the two are linked in subtle ways. Some ozone-depleting chemicals are also powerful greenhouse gases, and climate change can indirectly influence ozone loss by cooling the stratosphere, creating conditions that speed up ozone destruction over Antarctica.

Over the past 45 years, with developments in the industrial world, the ozone layer has been repeatedly damaged. According to Scientific American, the “ozone layer that scientists predict will recover the health it had in 1980 over the tropics and midlatitudes by 2040, over the Arctic by 2045, and over the Arctic by around 2066,” meaning that environmental policies are being shown to have a significant effect on the future of our stratospheric ozone. The greatest of these policies is named the “Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer,” signed by every country in the world, and working by terminating the harmful chemicals that break down the ozone layer; chemicals dating back to the early 1980s, such as Chlorofluorocarbon (CFC), which have been banned as aerosols all around the globe. Similar to the Montreal Protocol, the Vienna Convention was the formal beginning to “universal cooperation over the protection of the fragile ozone layer,” as per the UN News. As time has passed since these initial acts of the late 1980s, the ozone layer has had time to heal itself of its harmful chemicals, and it has been able to work towards a closure over the hole in the Antarctic layer caused by ozone-depleting.

While the self-healing process of the ozone layer is encouraging, signs of ozone recovery were expected due to the global action taken decades ago. The new signs of ozone depletion substances’ absence show the need for science-driven policymaking as well as international environmental cooperation. The ozone layer is on track to return to its 1980 levels within the next few decades; an achievement that would have been unimaginable without the Montreal Protocol–that is, if current policies remain as they are now. According to Susan Solomon and a study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, “By something like 2035, we might see a year when there’s no ozone hole depletion at all in the Antarctic,” and “some of you will see the ozone hole go away completely in your lifetimes. And people did that.” If people around the globe continue to act in a collective effort, the future of the Earth and its ozone layer looks hopeful.