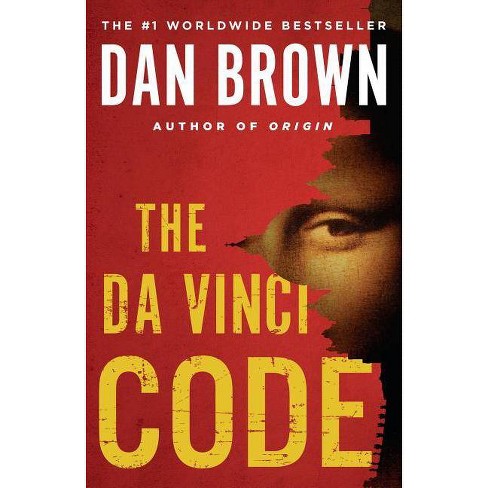

“The Greatest Showman” and the Problem with P.T. Barnum

January 5, 2018

On December 20th of 2017, mainstream audiences were introduced to P.T. Barnum (played by Hugh Jackman) in the form of the new Hollywood musical based on a true story—The Greatest Showman. It wasn’t the first time this story has been told: Barnum was a 1980 Tony-award winning musical that ran for about two years on Broadway.

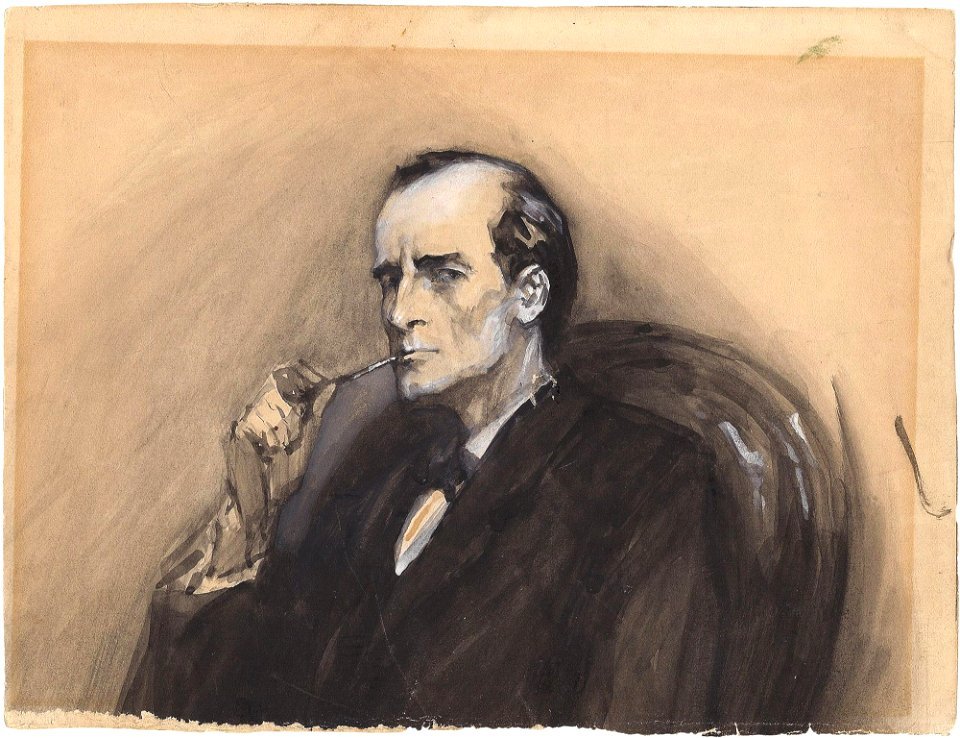

Barnum was a promoter and an entrepreneur who headed one of the most successful circuses of all time, so the existence of both the movie and the theatrical production would make sense. Where both of the aforementioned productions fall short, however, is how they carry through such a task.

The Greatest Showman’s P.T. Barnum is depicted as a champion of diversity—a man who accepts the “freaks” of society for who they are. Using this narrative as its central theme, the movie tells a tale of progressive values of equality with Barnum at center stage. With his ragtag crew of socially unaccepted misfits, he’s able to kickstart a hugely successful circus, later settling down with his family and passing on the mantle of ringmaster to the fictional Phillip Carlyle (played by Zac Efron). It’s a compelling story, and messages like that are truly necessary in today’s polarizing sociopolitical climate. The problem is, it isn’t true.

My issue isn’t that they didn’t adapt every part of Barnum’s narrative (the fact that the movie’s only “based on” a true story didn’t escape me). No, it’s more the parts they chose to ignore. You see, the real P.T. Barnum was an exploitative degenerate who would’ve likely cringed at the very idea of his likeness being used to celebrate egalitarianism if he didn’t think it could make him a buck or two. And it has: $93 million worldwide and counting, but that’s tangential.

Barnum actually wasn’t the hero of the marginalized that The Greatest Showman sets out to illustrate him as, but instead, a man who wouldn’t mind using those same marginalized individuals as tools to earn him fame and money. Case in point: Joice Heth. Heth was a black slave bought by Barnum in old age after her previous promoters found no luck in advertising her as the childhood nurse of George Washington. She was blind and almost completely disabled when Barnum started exhibiting her in 1835, and got the latter heaps of undeserved attention, kick-starting his career. Heth couldn’t even escape Barnum after death, though—after the matter of her age came into scrutiny in the public, Barnum enlisted a doctor to give her a public autopsy with fifty cents admission. It turned out she wasn’t the age of 161 (as Barnum had advertised her as), but 80. Let’s repeat that. P.T. Barnum, the main character of The Greatest Showman, quite literally used a disabled black woman to catapult himself to fame.

The movie doesn’t get into this, instead covering it up by doing things like changing Barnum’s “African giantess”—Madame Abomah—to a “tall man” Barnum pretends is Irish. The abuse of Barnum’s black performers was generally accepted in his time, but there’s absolutely no reason why it should be kept out of a mainstream adaptation because such abuse certainly isn’t overlooked now. This movie has no business making Barnum look like a moral figure, and certainly has no ground to stand on when making the case that he was a paragon of racial fairness.

Compounding this is the tone-deaf inclusion of the fictional Anne Wheeler (played by Zendaya). In her subplot, she falls in love with the previously mentioned Phillip Carlyle, an upper-class patrician, and the two ultimately prevail despite a hostile atmosphere of racial prejudice. The point of this, obviously, is to continue the perpetuation of the message of equality that the movie tells in its main plot. However, this attempt simply seems insulting. The film ignores Barnum’s real history of racism and instead creates two entirely fictional characters to justify his lack thereof.

It’s not like name recognition was doing The Greatest Showman any favors—considering that I haven’t seen many complaints from mainstream audiences about Barnum’s history of racial injustice—so I don’t understand why they couldn’t just change the names of the characters and instead very loosely adapt P.T. Barnum’s life as a ringleader if achieving racial equity was really the goal of the movie. Not only that, but a lot of the movie isn’t very accurate to Barnum’s real life, even when disregarding his racism. For example, neither Barnum’s relationship with Jenny Lind, his “affair” with her, nor even the timeframe of the movie are historically correct.

The large-scale inaccuracy of the film is likely why it hasn’t been torn to shreds by mainstream movie critics, but that’s the entire problem with The Greatest Showman. By continuing our disturbing historical trend of covering up the truth about our chosen heroes, we make truly combating racial discrimination and injustice more difficult. There’s an issue when the most dividing thing about this movie is whether its soundtrack is worth listening to.

In summary, P.T. Barnum was a scumbag who exploited minorities and the disabled—and by making him look like the epitome of virtue, The Greatest Showman only follows in the titular character’s footsteps by making its audience look like total suckers.